The news that President Joe Biden is releasing millions of barrels of oil from a federal stockpile raises a question. Well, a few actually. Namely, wait, what the hell? We have a huge stockpile of oil?

Even stranger still, a president who has put forward the most progressive climate policies in executive branch history (an admittedly low bar but still) is tapping said stockpile just months after setting a goal to reduce carbon emissions 50% in the next decade. What gives?

The stockpile, known as the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, has been around for decades. And its existence and the way presidents past and present have treated it tells us more about American energy history and the nation’s oily priorities than what the future could hold.

What is the Strategic Petroleum Reserve?

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve, or SPR, is a product of its time. The U.S. government first began stockpiling oil in the mid-1970s in response to that decade’s energy crisis. The crisis was precipitated by OPEC, which set up an oil embargo against the U.S. and other countries. That caused shortages and price spikes.

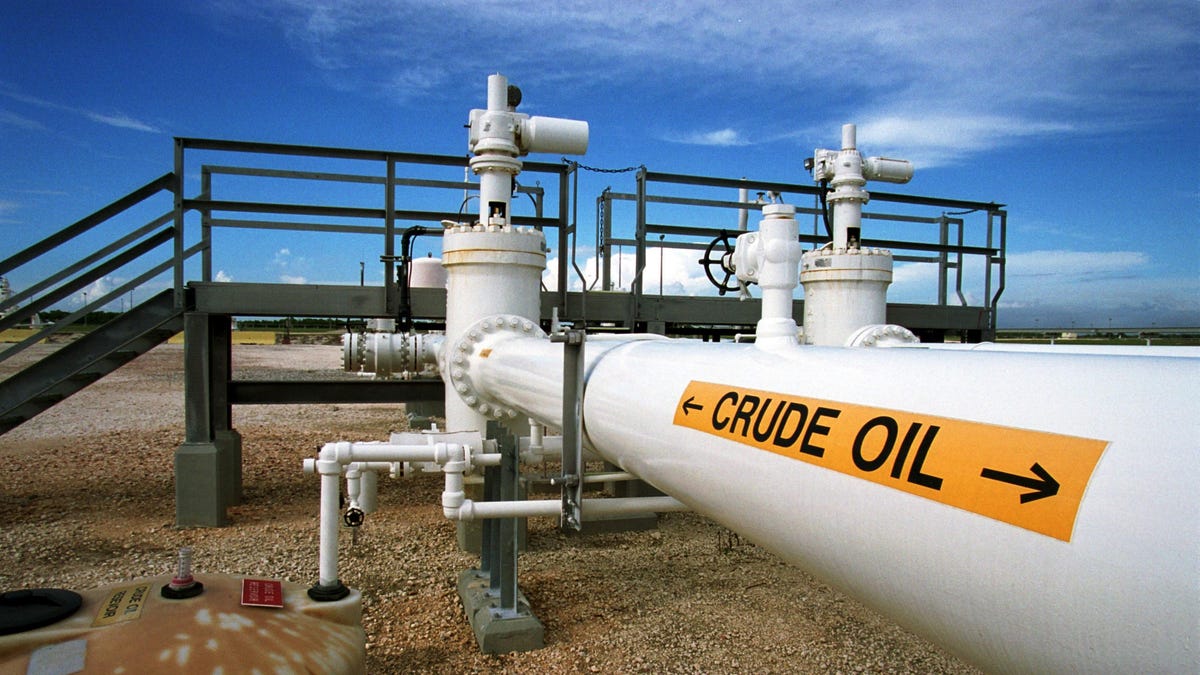

Enter the SPR, which was set up as a way to ensure that the U.S. could access crude in case of an emergency. In what feels like Cold War-esque twist, the SPR is stored in underground salt caverns—which the Department of Energy says is the cheapest and most secure form of oil storage—at four major sites around the Gulf Coast in Louisiana and Texas.

The 60 caverns altogether can hold 714 million barrels of oil; the largest cavern is big enough to comfortably hold Chicago’s Willis Tower, which stands at 1,450 feet (442 meters). There are currently around 620 million barrels of crude oil sitting in the reserve. That’s enough oil to keep the entire country running for about a month if every other form of production and import stopped suddenly.

Has the reserve ever been tapped before?

In a word, yes. But emergency sales coordinated with the International Energy Agency have been authorized only three times in the stockpile’s history, including once after Hurricane Katrina. The most recent emergency tap came in 2011 as the Arab Spring and Libyan civil war constrained supplies when former President Barack Obama released around 30 million barrels in 2011.

The reservoir has been tapped more frequently to help with supply chain shortages and hiccups in the U.S. Former President Donald Trump released 5.2 million barrels in the wake of 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, which knocked refineries and drilling operations along and in the Gulf of Mexico offline.

The Trump administration, though, also continually questioned the need for the SPR. It even proposed selling off half the reserves in 2017 in order to fill budget gaps. Yet when the pandemic hit, the administration ended up buying a lot of oil to fill the SPR as a way to stave off the catastrophe U.S. oil producers were experiencing after oil prices went negative last year.

Will Biden’s oil release lower gas prices?

Rather than plagiarize myself, allow me to redirect you here.

OK, but what about the climate?

It may seem counterintuitive to see Biden, who has made addressing climate change his calling card, encourage the release of more oil since burning fossil fuels is the main cause of the climate crisis. But the release reflects the tensions of the present, oil-constrained economy versus where Biden and numerous other world leaders want it to be in a decade.

The policies Biden has put in place in the executive branch along with his climate agenda that largely hinges on how Sen. Joe Manchin feels after his weekly call with Exxon’s lobbyists will pay carbon reduction dividends. But those benefits don’t mean the world will just stop using oil overnight.

“The president is between a rock and a hard place,” said Lorne Stockman, a director at Oil Change International.

Instead, what the SPR and our current economy reflect are the decades of success the oil industry has had in gumming up the political system and entrenching itself in our daily lives.

Now, instead of being in a place where we are able to use oil more sparingly and efficiently, “we’re locked into a high demand scenario,” Stockman said. “When we had the technology, and all we needed was policies to encourage more efficient oil use, the focus in the U.S. was instead the shale boom. There was no incentive to get demand down. There’s been a structural lack of focus on efficiency and demand that was bound to hit us in the face.”

We’re now getting whacked pretty hard. But the coming decade of decarbonization offers a chance to lower the burden on everyday folks and support oil workers. We might just need to navigate a few rough spots like the current one first.