Following a scare last week, NASA and European Space Agency officials have said they will continue launch preparations for the James Webb Space Telescope. The $10 billion instrument is slated to launch on a European-built Ariane 5 rocket no earlier than December 22.

NASA said that engineers have completed additional testing to ensure the telescope’s readiness for flight, and fueling operations began on November 25. The telescope has 20 small thrusters for maneuvering and will be filled with about 240 liters of hydrazine fuel and dinitrogen tetroxide oxidizer. The fueling process will take about 10 days.

The decision to press ahead with the Webb telescope’s launch countdown counts as good news after a slightly worrisome announcement one week ago. On November 22, NASA said it would delay the space telescope’s planned launch by a few days to investigate an “anomaly” during processing operations at the launch site in Kourou, French Guiana.

“Technicians were preparing to attach Webb to the launch vehicle adapter, which is used to integrate the observatory with the upper stage of the Ariane 5 rocket,” NASA said in a blog post. “A sudden, unplanned release of a clamp band—which secures Webb to the launch vehicle adapter—caused a vibration throughout the observatory.”

The problem occurred earlier in the month, and NASA convened an anomaly review board to investigate and conduct additional testing. Following those tests, engineers concluded that the observatory had not been damaged by the vibrations from the clamp band’s release.

The much-anticipated launch of the space telescope is only the beginning of the road for Webb to begin science operations, however. Its launch late this year will set up a nerve-wracking holiday season for NASA managers and the scientists who hope to use the powerful telescope to look back and see some of the earliest galaxies to form in the universe.

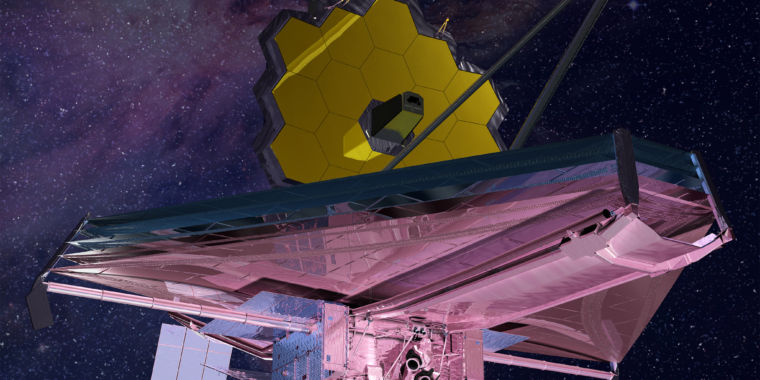

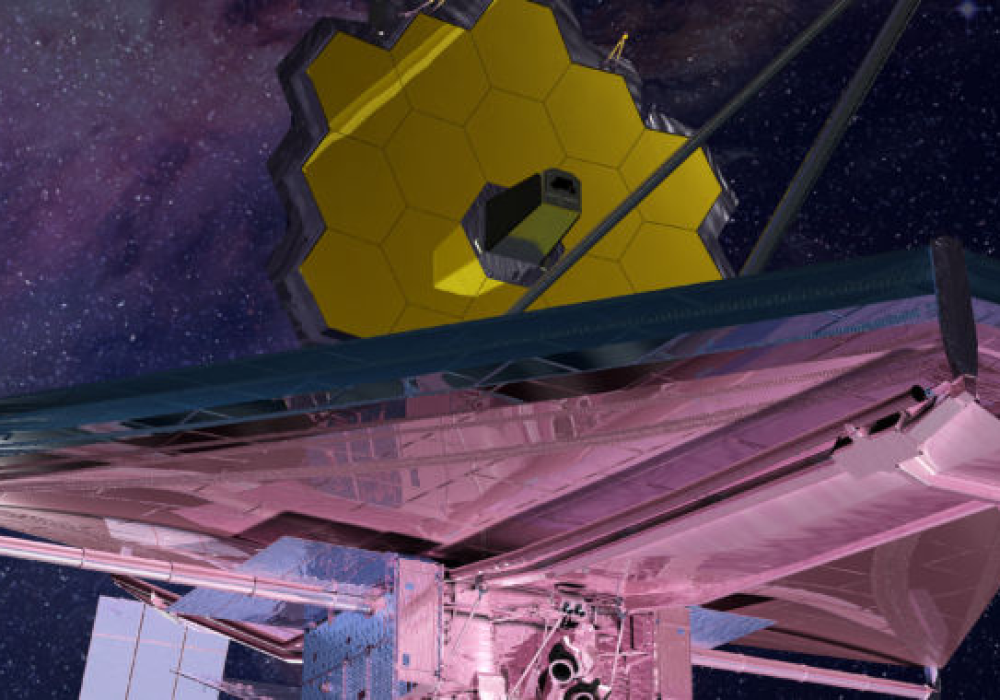

After its launch, Webb will need to travel about 1.5 million km from Earth to the L2 Lagrange Point beyond the Moon. There, it will be able to maintain a stable position without using much on-board propulsion. Along the way, and once there, some 50 deployments of the large, folded-up telescope will be necessary to prepare for scientific observations.

This process will involve nearly 350 single-point failures, and if something goes wrong, it would scuttle the deployment without hope of repair.