“It’s so unlike him. I’m really glad he did it,” Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) said of McConnell. “What’s the old saying? One flowering rose doesn’t make a spring. But I’ll take what we can get.”

McConnell “feels like in this circumstance at least, that they both have been working in good faith,” agreed Senate Minority Whip John Thune (R-S.D.). “The fact that they have been talking should be perceived by most to be a positive development.”

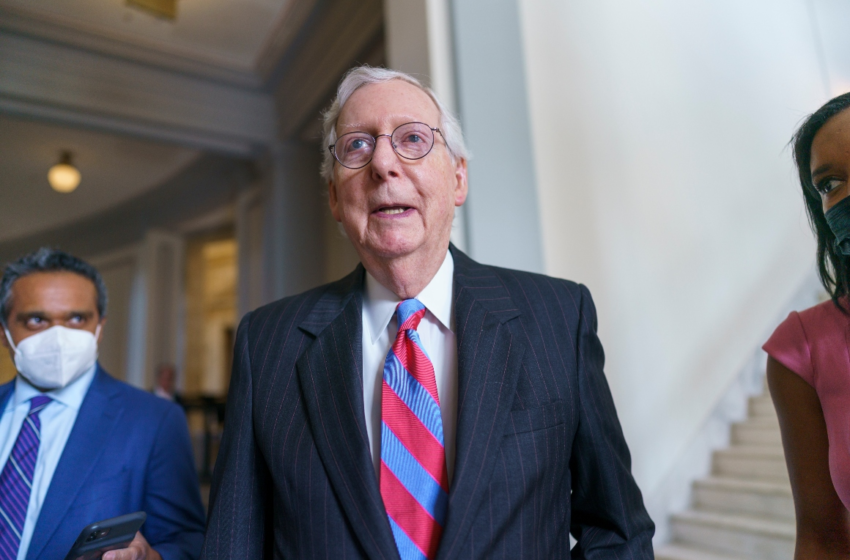

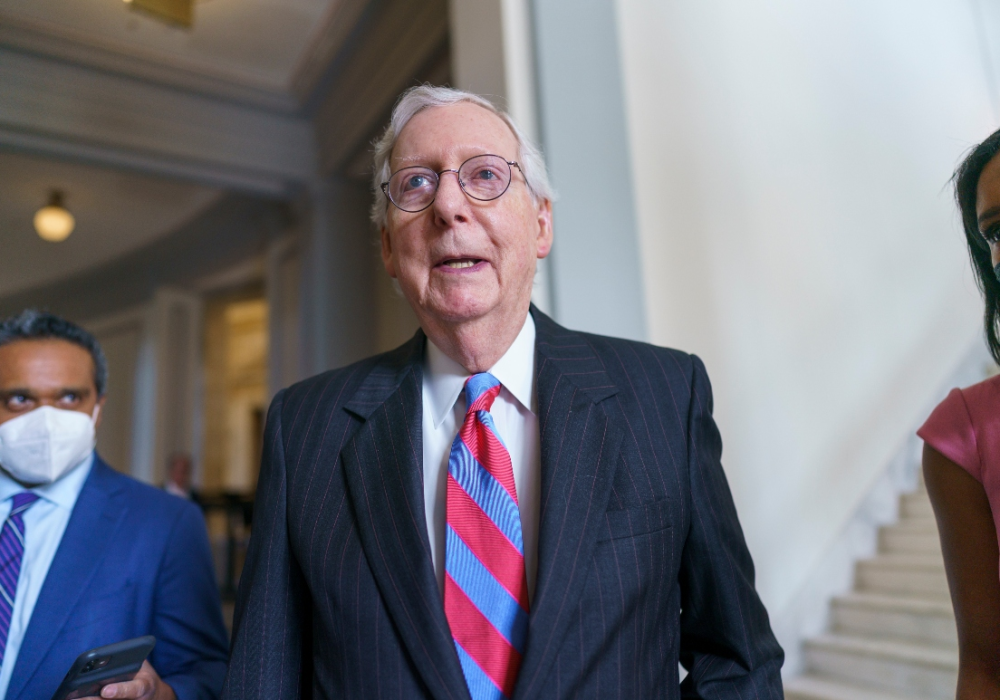

The debt deal comes on the heels of agreements between the Senate leaders to fund the government, complete a defense bill, pass a new infrastructure law and collaborate on a competitiveness bill. And it could mark the high point of Schumer and McConnell’s relationship. That says as much about the two pugnacious leaders as it does about the state of the Senate, which now sits leagues away from the days when the two party leaders met regularly.

Schumer’s tenure as majority leader began this year with McConnell’s refusal to give him an organizing resolution to run the Senate for weeks, the first in a series of McConnell’s challenges to Schumer’s leadership of a 50-50 Senate. But nothing rivaled the standoff that McConnell initiated this summer when he pledged that not a single Republican would vote to raise the debt limit.

That the dispute is ending with a deal between Schumer and McConnell to kick the issue past the midterms is nothing short of shocking for many in the Senate considering McConnell’s vows not to assist Democrats. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) helped grease the wheels, speaking to McConnell repeatedly and one day visiting Schumer and the GOP leader back-to-back.

“I’m encouraged,” Manchin said on Wednesday after complaining all year about how the brash New Yorker and the taciturn Kentuckian didn’t talk enough. “We’ve just got to work together.”

Some would like to see more. Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) has suggested to the White House that President Joe Biden regularly host congressional leaders in both chambers for weekly discussions, according to a source familiar with her request. That shows no signs of happening.

The talks between McConnell and Schumer on the debt ceiling were so delicate that even most senators experienced an information blackout. While lawmakers saw the mid-November talks as a positive sign, neither McConnell nor Schumer clued in their leadership team on the details until Tuesday. Hours later, the House approved a plan that allows Senate Democrats to raise the debt limit without Republican help. The Senate will take that up Thursday.

At first, congressional leaders wanted to fold the debt limit into the annual defense policy bill. After the second meeting with McConnell, Schumer warned Pelosi that the leading option at the time, combining the debt limit with a defense bill, would only work if the House sent over the legislation before Dec. 7. House GOP Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s opposition put an end to that, so congressional leaders instead rolled the debt limit into legislation preventing Medicare cuts.

The agreement gives the leaders the ability to save face with their respective caucuses. Schumer can say that Democrats can now fully focus on clinching Biden’s agenda and resisted the GOP push to use the often convoluted process known as reconciliation to address the matter. During his talks with McConnell, Schumer reassured his members that he would not deviate from that position, according to a Democratic senator.

McConnell, meanwhile, can say Democrats lifted the debt limit by themselves and voted for an approximately $2 trillion increase, potential fodder for GOP campaign ads in the midterms. He’s also removing a Democratic argument to change the legislative filibuster after the majority party threatened rules changes over the debt ceiling.

The politics for McConnell are more complicated. While he’s confident he has the necessary 10 Republican votes to pass the measure, he won’t get the unanimous support that Schumer will receive from Democrats in Thursday’s critical procedural vote. After his party unanimously blocked a debt ceiling increase in September from coming to the Senate floor, the GOP enters Thursday’s vote divided.

“It’s a terrible deal,” said Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas). “I don’t think Republicans should be in any way complicit in the Democrats’ reckless spending.”

And Democrats have plenty of questions about why this deal wasn’t reached earlier to save several months of drama. Throughout the process, Pelosi mostly deferred to Schumer because the Senate was always the problem. But House Democrats vent that the bout between Schumer and McConnell required them to walk the plank and vote on debt ceiling legislation five times, according to Democratic sources.

The likely answer for the delay comes down to McConnell’s initial hard-line position and Schumer’s refusal to bow to his demands. In September, Schumer accused McConnell of “spinning a tale, a web of subterfuge, deception and outright contradictions” on the debt ceiling. McConnell in turn penned a letter to Biden in October after he helped raise the debt ceiling for two months, referring to a speech Schumer delivered as a “tantrum” that “encapsulated and escalated a pattern of angry incompetence.”

But recently the leaders are using a far more conciliatory tone. Schumer said Wednesday that he and the GOP leader had “fruitful, honest and good discussions” when it came to the debt limit, while McConnell said he and Schumer “reached a conclusion that I think worked for both sides.” It continued a pattern of fading personal animus, for the moment.

When members of McConnell’s caucus threatened to temporarily shut down the government over President Joe Biden’s vaccine mandate or hold up the defense policy bill, Schumer opted to single out individual members rather than blame McConnell for their actions. Still, no one is expecting the good vibes between the two leaders to last.

With the debt limit out of the way, Democrats and Republicans will focus on Biden’s social spending bill — and what the two leaders have to say about each other’s priorities probably won’t be pretty.

“Robert C. Byrd one time said that the Senate is a place where you can be working with somebody one day,” said Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), a top McConnell deputy, “and fighting them tooth and nail the next.”

Heather Caygle contributed to this report.