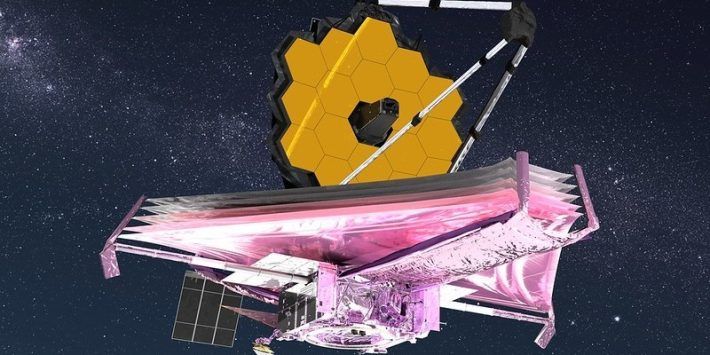

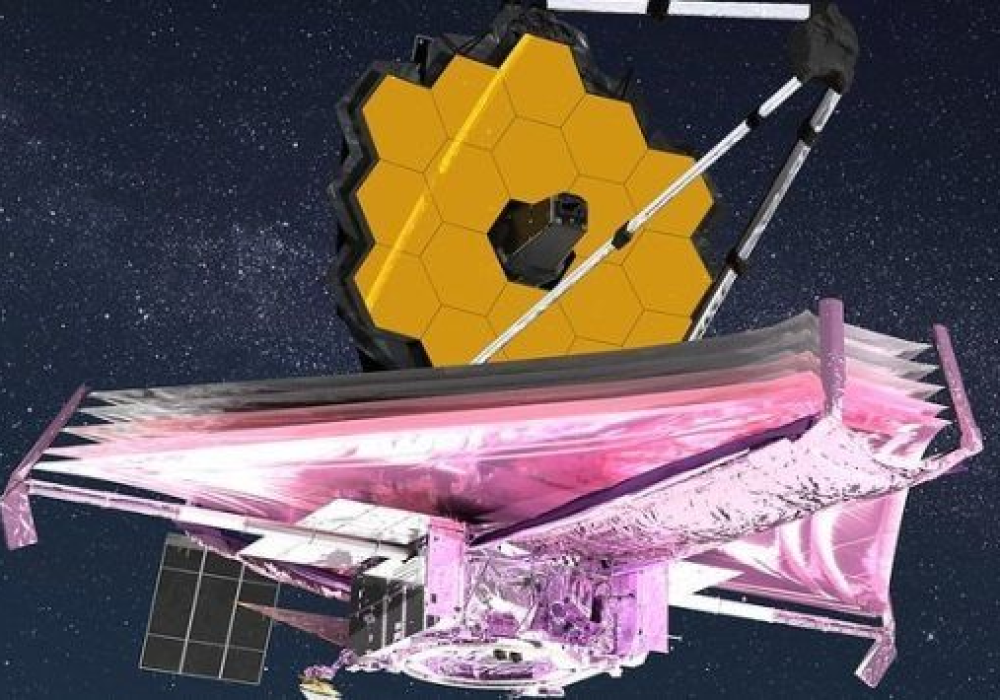

The James Webb Space Telescope has successfully deployed all five layers of its tennis-court-sized sunshield, a prerequisite for the telescope’s science operations and the most nerve-wracking part of its risky deployment.

The challenging procedure, which required careful tensioning of each of the five hair-thin layers of the elaborate sunshield structure was a seamless success today (Jan. 4). Its completion brought huge relief to the thousands of engineers involved in the project over its three decades of development, as well as the countless scientists all over the world who eagerly await Webb’s groundbreaking observations.

“Yesterday, we did not think we were going to get through the first three layers,” Keith Parrish, the observatory manager for the James Webb Space Telescope, said in a live NASA webcast during today’s deployment. “But the team just executed everything flawlessly. We were only planning to do one yesterday, but that went so well. They said hey, can we just keep going? And we almost had to hold them back a little bit.”

Related: A James Webb Space Telescope astronomer explains how to send a giant telescope to space — and why

Securing the right tension for each of the sunshield’s five layers was achieved today using a complex system of cables and motors pulling at the corners of the diamond-shaped sunshield.

The elaborate tightening of the sunshield’s diamond-shaped layers began on Monday (Jan. 3). NASA originally expected each layer to take one day, but by the end of the first day, three layers were successfully tensioned with the final two tightened on Tuesday (Jan. 4).

The successful deployment of the fourth layer was confirmed at 10:23 a.m. EST (1523 GMT) as the telescope cruised some 546,000 miles (879,000 kilometers) from Earth. The final, fifth layer, was tensioned at 12:09 p.m. EST (1709 GMT) and was met with cheers and applause from control teams.

“This is a really big moment, I just want to congratulate the entire team,” one of the operations managers could be heard saying in the webstream upon confirmation of the fifth layer being completed. “We still have got a lot of work to do, but getting the sunshield deployed is really, really big.”

This sunshield deployment was thoroughly tested on Earth but even the most high-tech test lab can’t fully simulate the effects of weightlessness and other factors present in outer space. If anything went wrong, the entire mission, which cost $10 billion and took roughly three decades to build, could have been in jeopardy.

The James Webb Space Telescope is designed to study the universe in the infrared wavelengths and therefore has to be extremely cold for its sensitive detectors to work as designed.

Since Webb observes infrared light, or heat, it has to be kept at extremely cold temperatures so that there is no heat from Webb that could obscure its observations. By reflecting both incoming solar radiation and heat from planet Earth, the sunshield keeps Webb perfectly cold.

With the ultimate goal to detect the extremely faint light coming from the most distant stars and galaxies, those that lit up the dark universe in the first hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang, Webb’s detectors need to be extremely sensitive. Any heat from the telescope would dazzle those detectors and outshine that faint precious signal.

“We get about a 100 degree Fahrenheit (55 degrees Celsius) drop per layer,” Parrish said. “We get about 600 degrees F (330 degrees C) between the hot side and what I call our coldest temperature on the observatory, the instrument detectors,” which are running at around minus 400 degrees F (minus 235 degrees C), he added.

Against all obstacles

The challenging operation was conducted as humans on Earth contend with a new surge of the COVID-19 virus brought about by the recently discovered Omicron variant, which forced many team members into isolation.

“One of the things that has been a challenge is people who worked a long time on this, and we had to isolate them,” Parrish said. “Fortunately, in this day and age, we can get them hooked up to our operations loop and they can help us remotely from wherever they are.”

The James Webb Space Telescope is heading for what is known as the Earth-sun Lagrange Point 2 (L2) some 930,000 miles (1.5 million km) away from the planet. L2 is one of five points between the sun and Earth where the interplay of the gravitational forces of the two bodies keeps an object in a stable position with respect to the two bodies. The James Webb Space Telescope will thus orbit the sun, permanently aligned with Earth, hiding from the star’s scorching rays.

With the sunshield now fully unfurled and tensed, the operations teams will move on to the deployment of the telescope’s secondary mirror.

“Starting this evening, we’re going to get some heaters on to start heating up the motors that actually do the deployment of our secondary mirror system,” said Parrish. “We’ll get that heated up and we’ll get on with that.”

Webb will reach L2 by the end of January. Once the scope arrives, it will be fully deployed, including its 21 feet 4 inches-wide (6.5 meters) primary mirror, which too had to be folded for launch because of its large size.

The mirror’s 18 gold-coated hexagonal segments will take 100 days to cool down to their operational temperature. Only after that will they be carefully aligned so that the seams between them are completely smooth, allowing astronomers to take sharp images of the most distant universe. First images from the telescope, the most complex and expensive space observatory ever built, are expected in the summer of 2022.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.