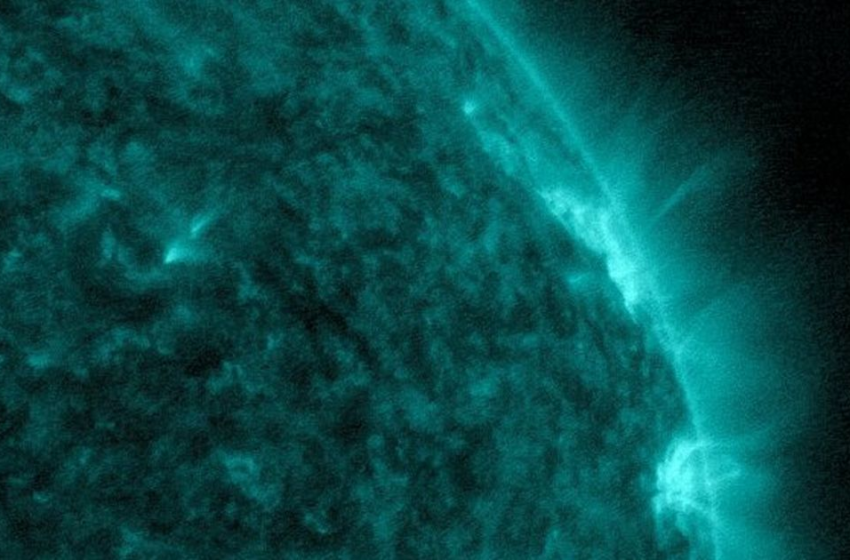

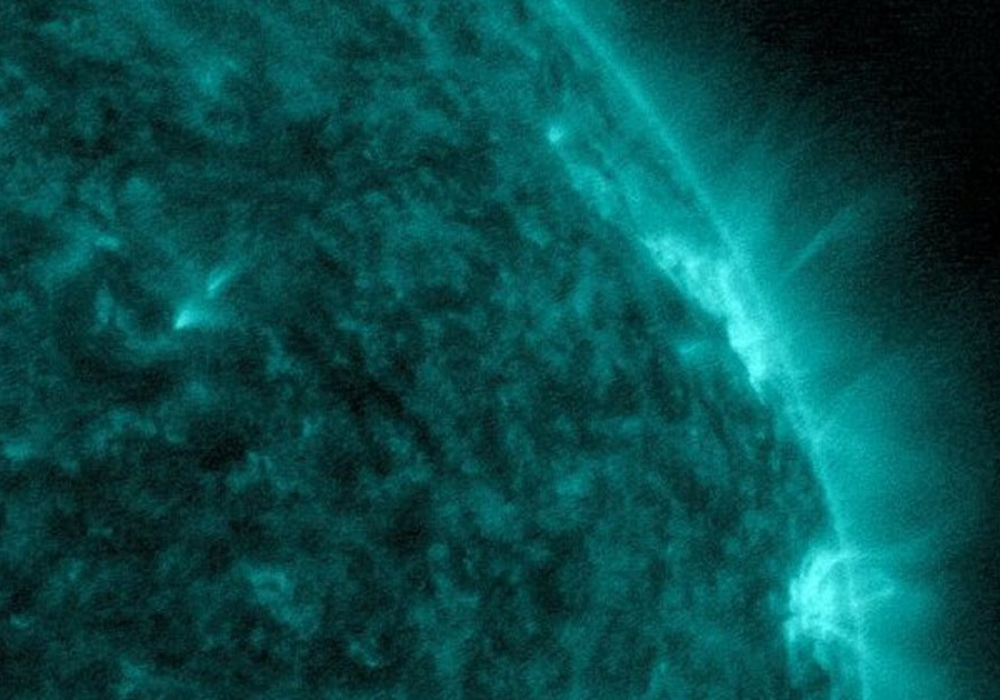

The sun emitted a midlevel solar flare on Jan. 20, 2022, peaking at 1:01 a.m. EST. NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory, which watches the sun constantly, captured an image of the event.

NASA/SDO

On Thursday, our sun released its pent-up energy in the form of a little magnetic bomb. It’s called a solar flare, and NASA caught the whole thing on camera.

Solar flares, which are sudden explosions on the sun’s surface caused by strong magnetic forces, are of concern to astronomers because these events can impact electrical power grids on Earth, causing regional blackouts. They also risk interference with radio communications.

Get the CNET Science newsletter

Unlock the biggest mysteries of our planet and beyond with the CNET Science newsletter. Delivered Mondays.

“This event, in particular, disrupted radio communications over the Indian and Pacific oceans — so its likely biggest impact was a disruption of maritime communications,” said Jesse Woodroffe, a program scientist and expert in space weather at NASA.

Even more jarring is if astronauts are in the flares’ line of fire, such detonations may greatly threaten space traveler and spacecraft safety. The good news, though, is NASA categorized the recent flare as a category M5.5 midlevel eruption, which corresponds to both a moderate severity and radio blackout threat for the side of the planet facing the burst.

“It’s not exceptionally strong in the grand scheme of things,” Woodroffe said, “but it nevertheless can have significant effects depending on what portion of the Earth is sunlit at the time of the flare.”

For now we can just sit back and admire the spectacular image captured by the agency in “extreme ultraviolet light,” colorized in an absolutely mesmerizing teal blue.

Around 300 M-class flares occur during each solar cycle, and they’re most likely to occur near solar maximum, a point we’re steadily approaching, according to Woodroffe. “Right now this is shaping up to be a much more active and interesting solar cycle than the last one. That means that we could be in store for solar activity the likes of which we haven’t seen in nearly 20 years.”

You can see the solar flare’s flash on the right side.

NASA/SDO

What causes a solar flare?

Instead of a glowing orb, think of the sun as a giant, flaming, spherical ocean. This ocean is so ridiculously hot, at 5,778 Kelvin (9940.73 Fahrenheit), that would-be atoms on the star are completely blasted apart into a gaseous mixture of ions and electrons called a plasma.

These particles, with varying positive and negative charges, work together to form the sun’s magnetic field lines, thereby deciding how the boiling ocean moves around. Think of it as a sort of immensely strong, magnetic soup — more precisely, picture a chicken noodle soup. The noodles are the sun’s magnetic fields.

However, just as stirring your soup in search of a baby carrot can tangle your noodles, these charged-up, magnetic lines can grow tangled, most often near sunspots. Eventually, as regions of the spaghetti-like magnetic fields form complex knots and push and pull on each other, they experience an energy overload.

That forces them to explode into space, revealing a fiery loop on the side of our enormous star, called a solar flare.

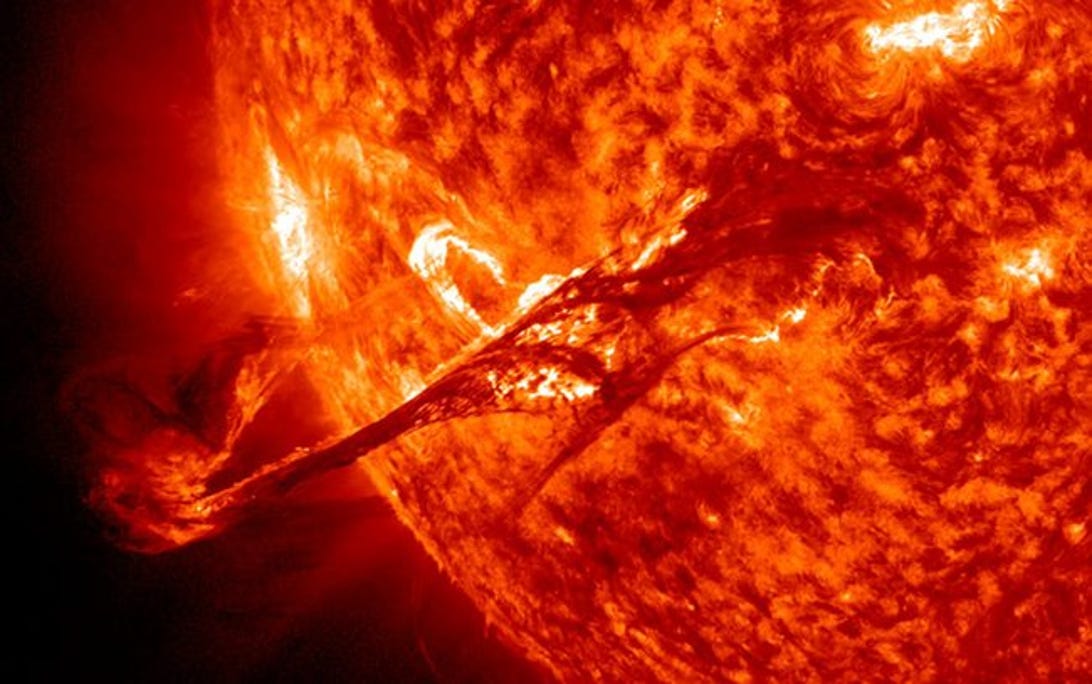

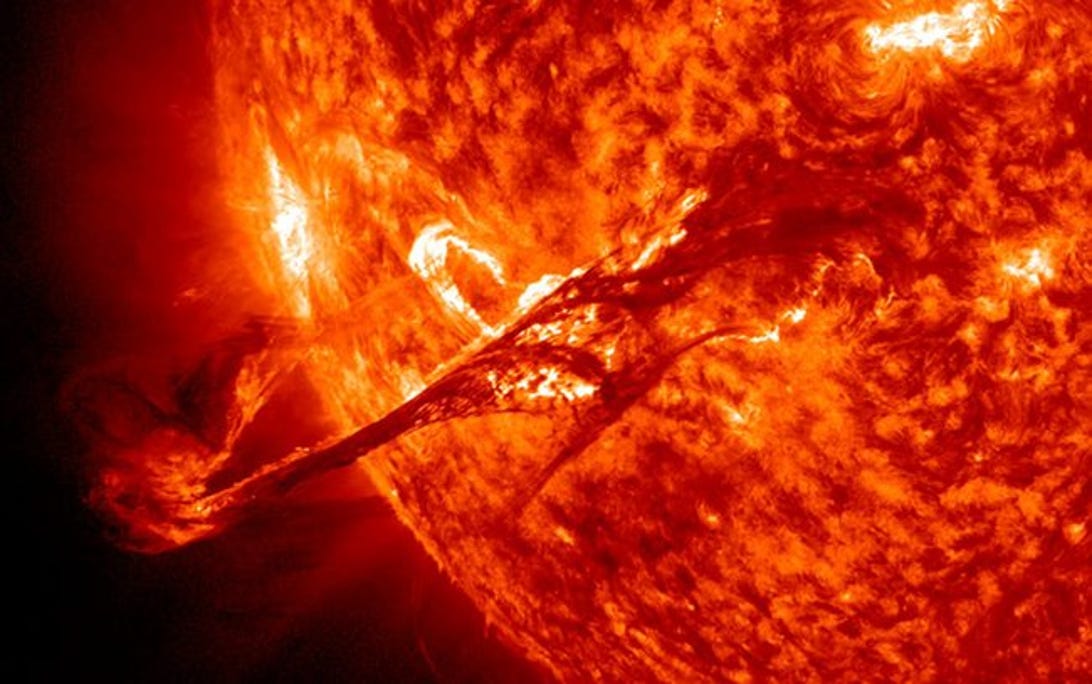

The sun sent out a huge solar flare in August of 2012

AIA/SDO/Goddard Space Flight Center/NASA

“There is also a potential for solar flares to cluster, meaning the occurrence of one could presage the appearance of more, potentially stronger flares,” Woodroffe said. “Thus, monitoring for events such as this is important because it could be the precursor of something more serious.”

And sometimes, the fiery loop stretches out until it becomes taut enough to sort of snap off, resulting in a coronal mass ejection. “A coronal mass ejection is, in essence, a little bit of the sun that gets blown off and sent flying into space towards Earth,” Woodroffe said.

Once it snaps off, the ejected portion heads directly toward our planet, picking up space-borne particles along the way and causing what’s called a solar storm. Thankfully, Earth’s atmosphere protects us from the brunt of the charged particles, with only relatively few getting caught in our planet’s shield. When that happens, though, we look up at these trapped, zippy particles in awe.

They appear to us as the Northern Lights.

“I don’t know if there was a coronal mass ejection associated with this flare, but we are expecting the possible arrival of a coronal mass ejection associated with a flare that occurred on Jan. 18,” Woodroffe said. “So, even if it’s not because of this flare, we could very well see some nice auroras this weekend.”

ESA astronaut Thomas Pesquet captured a stunner of a view of an aurora during a full moon in September 2021.

Thomas Pesquet/ESA