Spotify arrived more than a decade ago with an appealing proposition: Listeners could leave their CDs and downloads behind and stream virtually every song ever released. It made the platform a top power in the music business and ushered in competitors like Apple Music, Amazon Music and Tidal, helping reverse the industry’s nosedive.

Spotify remains the biggest music streaming service. But a few years ago it pivoted to add a buzzy format to its portfolio: podcasts. The move made the service a smorgasbord of audio entertainment — part music service, part news outlet, part always-on gabfest. It may have also set the company on a collision course with artists, and left listeners with a less-than-complete library of songs.

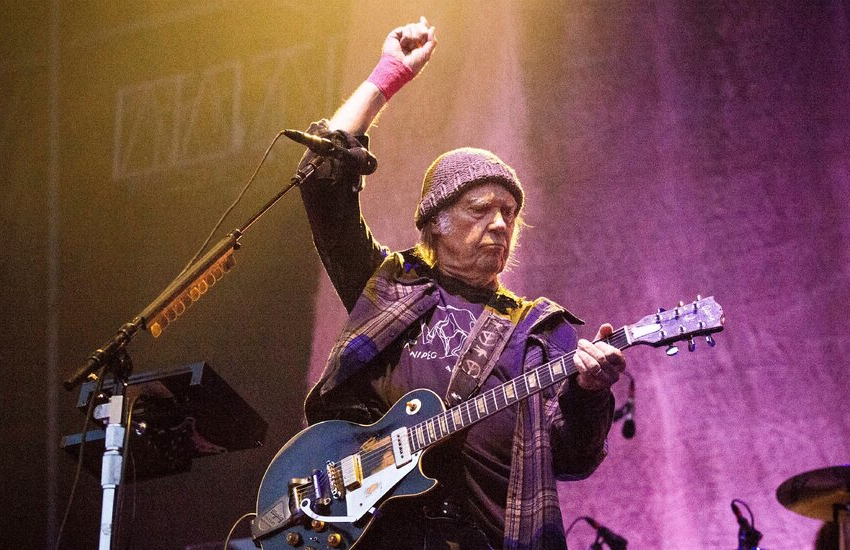

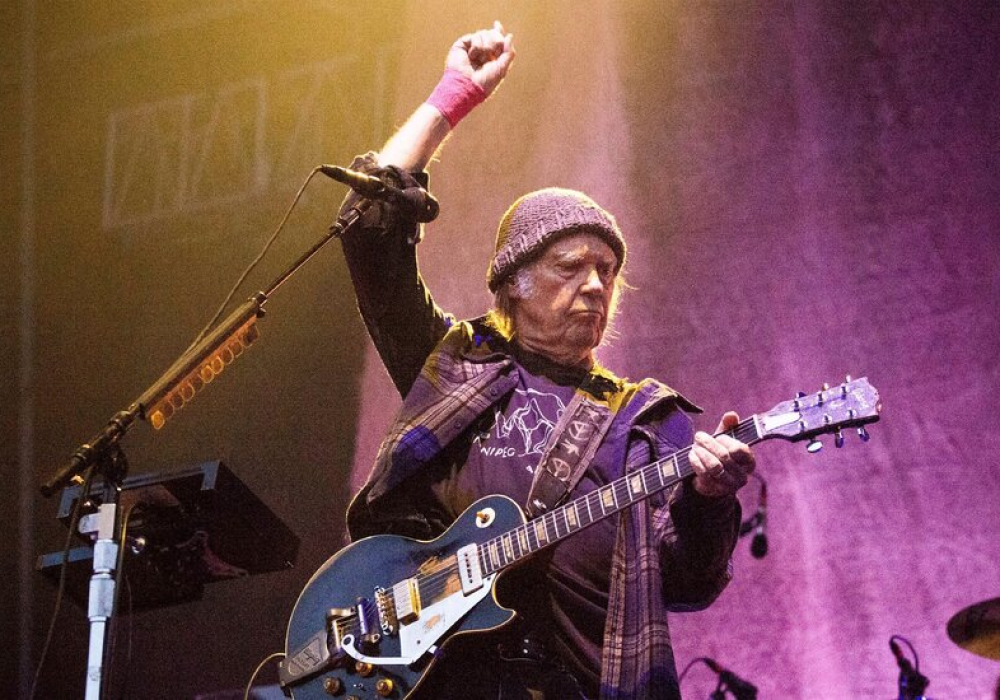

Last week, Neil Young kicked off a storm in the music business and on social media when he demanded that his music — including rock classics like “Heart of Gold” and “Cinnamon Girl” — be removed from Spotify. He was protesting the company’s support of Joe Rogan, its star podcaster, who has been criticized for promoting misinformation about the coronavirus and vaccines.

Even in an era when tech companies like Twitter, YouTube and Facebook are constantly policing content about Covid-19 on their platforms — and facing blowback from both sides of the free-speech debate for doing so — it was a rare instance of a top musician taking a stance that would affect his bottom line. Young said that 60 percent of his streaming income comes from Spotify.

He was quickly followed by Joni Mitchell, another musical icon whose cultural influence far exceeds her commercial impact online. Then the R&B singer India.Arie and two musicians who have played with Young — the guitarist Nils Lofgren and Graham Nash — said they would also pull their music from Spotify in solidarity.

Young’s withdrawal led to quick marketing moves by Spotify’s competitors. Apple advertised itself as “the home of Neil Young,” and SiriusXM revived a Neil Young channel.

So far the commercial impact of the controversy is unclear. Many users have taken to social media to declare they were canceling their subscriptions. The company may well face questions about this from Wall Street analysts when it announces its fourth-quarter earnings report on Wednesday.

On Sunday, after most of Young and Mitchell’s music was taken down, Daniel Ek, Spotify’s chief executive and co-founder, published the service’s platform rules and said Spotify would add “content advisory” flags on podcast episodes about the pandemic. “It is important to me that we don’t take on the position of being content censor,” Ek said. In a video, Rogan promised to offer more “balance” on his show, and said he was a fan of Young’s and Mitchell’s (though he mixed Mitchell up with the singer Rickie Lee Jones).

Whether that will be enough to quell a further artist revolt is yet to be seen, though Young’s gauntlet immediately became a cultural talking point. On Tuesday’s episode of “The View,” on ABC, Joy Behar called on younger stars like Taylor Swift to choose sides. “Let’s see some young people do it,” Behar said. “Let’s see Taylor and those guys take a stand.”

Even the White House has weighed in. At a news briefing on Tuesday, press secretary Jen Psaki was asked about Spotify’s response and said: “This disclaimer, it’s a positive step, but we want every platform to continue doing more to call out mis- and disinformation, while also uplifting accurate information.”

For longtime observers of Spotify, the Young episode is the latest strain in the company’s complex and frequently troubled relationship with artists. Much of that trouble has been over money. In 2014, Swift removed her entire catalog from Spotify, saying that the service’s “freemium” model — it has an ad-supported tier that lets users listen for free, and offers paid subscriptions to remove ads and add other perks — because, she believed, it did not fairly compensate artists for their work; it was nearly three years before she added her music back.

Recently, many musicians have spoken out over what they see as the unfairness of the streaming model overall — in which each stream usually generates just a fraction of a cent in payments — though Spotify and YouTube have borne the brunt of that critique.

Spotify has stumbled over questions of censorship before. In 2018, it briefly attempted to remove from playlists songs by R. Kelly and the rapper XXXTentacion — who had both been accused of sexual misconduct — through a “hateful conduct” policy, but canceled the initiative after an outcry in the industry.

But Spotify is no longer so easy for any artist to walk away from. Streaming now accounts for 84 percent of sales revenues in the United States, according to industry data, and Spotify has 172 million paying subscribers — about 31 percent of the worldwide total, and more than double that of its closest competitor, Apple Music, according to Midia Research, a market research firm.

That has made Spotify a key financial partner of record companies, and a “necessary evil” for artists, said George Howard, an associate professor at the Berklee College of Music and a former record and digital music executive.

“Not many artists would say, ‘I love Spotify,’” Howard said. “But many labels, whether they like or dislike Spotify’s values, are absolutely delighted by the fire hose of money that has flowed to them.”

Misinformation and the Spotify-Joe Rogan Controversy

Platform or media company? Spotify says it isn’t responsible for content posted on its platform, as social networks have argued for years. But since Spotify paid for the exclusive rights to Mr. Rogan’s show, critics say that puts an extra onus on the company to take responsibility.

Spotify stars have leverage. Spotify makes most of its money from subscriptions, so it would suffer financially if there were a wave of cancellations. That means Spotify needs to have popular content in its library, so musicians could force change by removing their music, as Neil Young and Joni Mitchell have done.

Rogan’s position within Spotify’s business has made his show, “The Joe Rogan Experience,” an important target for critics. While many podcasts are distributed widely to multiple platforms, Rogan’s is exclusive to Spotify, after a 2020 licensing deal that has been reported to be worth $100 million or more, though Spotify has never confirmed that figure. As critics see it, that makes Spotify the publisher of Rogan’s show, and therefore acutely responsible for it.

So far, some of the sharpest responses to Spotify have come from its own podcast hosts. On Monday, the hosts of “Science Vs,” another Spotify podcast, said on Twitter that the company’s support of Rogan “has felt like a slap in the face,” and announced that the show would comb through the claims made by Dr. Robert Malone, a guest on Rogan’s show on Dec. 31, whose remarks drew a sharp rebuke from public health experts. The author Brené Brown, whose Spotify shows like “Unlocking Us” have been heavily promoted by the company, said over the weekend that she will not be releasing any further podcasts “until further notice.”

Few expect a stampede of musicians to leave the service, especially major new artists, given the primary role that Spotify plays in getting their music heard and in driving much of their other business, like touring.

“It would take a really brave new frontline artist to go, ‘I’m going to say something which might antagonize half my fan base,’” said Mark Mulligan of Midia.

One kink may be whether artists have the contractual right to remove their music. Their recordings are typically controlled by record companies, which strike licensing deals with online services like Spotify.

Some artists’ contracts with their labels may give them the right to pull their music from online outlets for certain reasons, but others don’t, said Jeffrey M. Liebenson, a lawyer who has represented both record companies and digital services. And even if those rights are exercised, a service could raise objections to a mass exodus.

“Sometimes, the label can request a takedown if there’s a bona fide artist relations issue,” Liebenson said. “But the platform can get a little concerned: ‘Are they doing this because they have a legitimate artist relations issue, or are they waging a war against us?’”

In a public statement last week, Young thanked his record label, Reprise Records, a division of the Warner Music Group, as well as his music publishers, for standing by him. He also shot a flare up for other artists to follow his lead, but seemed to know already that their numbers may be small.

“I sincerely hope that other artists can make a move,” Young wrote, “but I can’t really expect that to happen.”