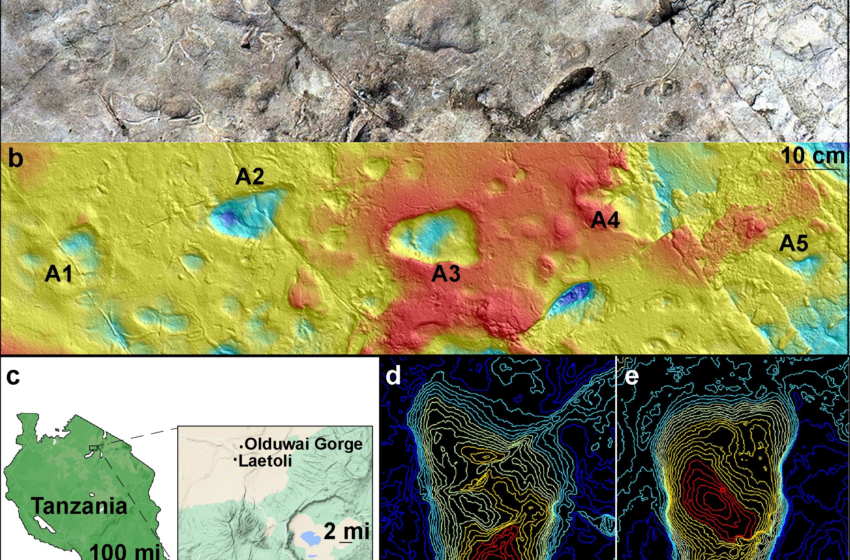

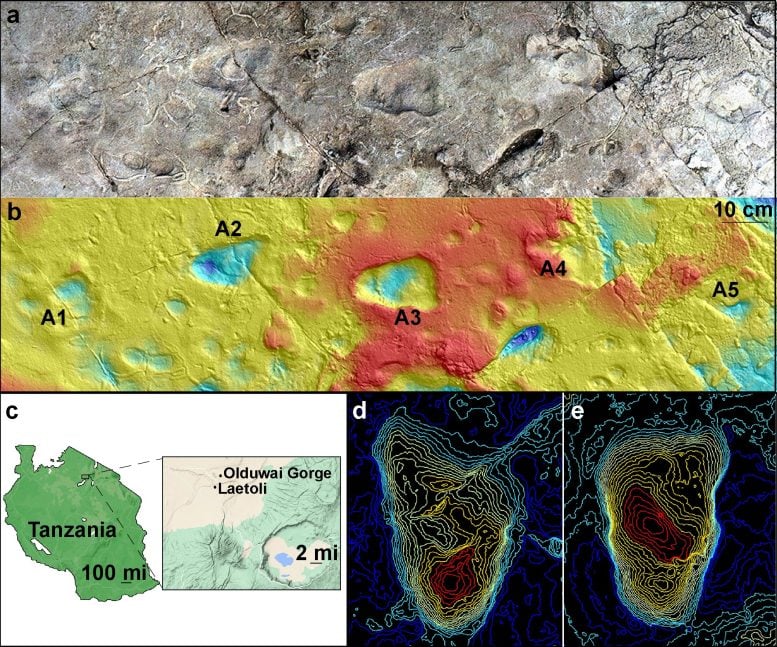

Model of Laetoli Site A using photogrammetry showing five hominin footprints (a); and corresponding contour map of the site at Laetoli, Tanzania, generated from a 3D surface scan (b); map showing Laetoli, which is located within the Ngorongoro Conservation Area in northern Tanzania, south of Olduvai Gorge (c); topographical maps of A2 footprint (d) and A3 footprint (e). Credit: Images (a) and (b) by Austin C. Hill and Catherine Miller. Image (c): Illustration using GoogleMaps by Ellison McNutt. Images (d) and (e) by Stephen Gaughan and James Adams

Findings provide conclusive evidence that multiple species of hominins co-existed on the landscape.

The oldest unequivocal evidence of upright walking in the human lineage are footprints discovered at Laetoli, Tanzania in 1978, by paleontologist Mary Leakey and her team. The bipedal trackways date to 3.7 million years ago. Another set of mysterious footprints was partially excavated at nearby Site A in 1976 but dismissed as possibly being made by a bear. A recent re-excavation of the Site A footprints at Laetoli and a detailed comparative analysis reveal that the footprints were made by an early human— a bipedal hominin, according to a new study reported in Nature.

“Given the increasing evidence for locomotor and species diversity in the hominin fossil record over the past 30 years, these unusual prints deserved another look,” says lead author Ellison McNutt, an assistant professor of instruction at the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Ohio University. She started the work as a graduate student in Ecology, Evolution, Environment, and Society at Dartmouth College, where she focused on the biomechanics of walking in early humans and utilized comparative anatomy, including that of bears, to understand how the heel bone contacts the ground (a foot position called “plantigrady”).

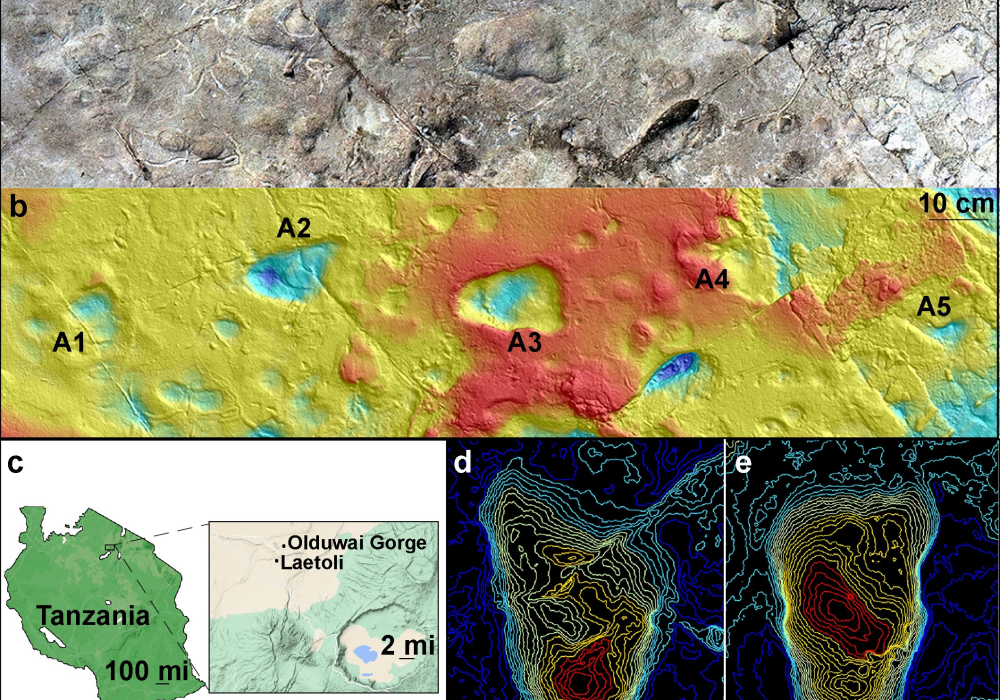

Image of Laetoli A3 footprint (on left) and image of a cast of Laetoli G1 footprint (on right). Analysis shows similarities in length of Laetoli A3 and G footprints but differences in forefoot width with the former being wider. Credit: Image on left by Jeremy DeSilva and on right by Eli Burakian/Dartmouth

McNutt was fascinated by the bipedal (upright walking) footprints at Laetoli Site A. Laetoli is famous for its impressive trackway of hominin footprints at Sites G and S, which are generally accepted as Australopithecus afarensis—the species of the famous partial skeleton “Lucy.” But because the footprints at Site A were so different, some researchers thought they were made by a young bear walking upright on its hind legs.

To determine the maker of the Site A footprints, in June 2019, an international research team led by co-author Charles Musiba, an associate professor of anthropology at University of Colorado Denver, went to Laetoli, where they re-excavated and fully cleaned the five, consecutive footprints. They identified evidence that the fossil footprints were made by a hominin—including a large impression for the heel and the big toe. The footprints were measured, photographed and 3D-scanned.

The researchers compared the Laetoli Site A tracks to the footprints of black bears (Ursus americanus), chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), and humans (Homo sapiens).

On left: Ellison McNutt collects data from a juvenile female black bear (Ursus americanus), who walks bipedally, unassisted through the mud trackway at Kilham Bear Center in Lyme, New Hampshire. On right: Left footprint from one of the juvenile male black bears. Credit: Image on left by Jeremy DeSilva. Image on right by Ellison McNutt

They teamed up with co-authors Ben and Phoebe Kilham, who run the Kilham Bear Center, a rescue and rehabilitation center for black bears in Lyme, New Hampshire. They identified four semi-wild juvenile black bears at the Center, with feet similar in size to that of the Site A footprints. Each bear was lured with maple syrup or apple sauce, to stand up and walk on their two hind legs across a trackway filled with mud to capture their footprints.

Over 50 hours of video on wild black bears was also obtained. The bears walked on two feet less than 1% of the total observation time making it unlikely that a bear made the footprints at Laetoli, especially given that no footprints were found of this individual walking on four legs.

As bears walk, they take very wide steps, wobbling back and forth,” says senior author Jeremy DeSilva, an associate professor of anthropology at Dartmouth. “They are unable to walk with a gait similar to that of the Site A footprints, as their hip musculature and knee shape does not permit that kind of motion and balance.” Bear heels taper and their toes and feet are fan-like, while early human feet are squared off and have a prominent big toe, according to the researchers. Curiously, though, the Site A footprints record a hominin crossing one leg over the other as it walked—a gait called “cross-stepping.”

“Although humans don’t typically cross-step, this motion can occur when one is trying to reestablish their balance,” says McNutt. “The Site A footprints may have been the result of a hominin walking across an area that was an unlevel surface.”

Ellison McNutt collects data from a juvenile female black bear (Ursus americanus), who walks bipedally, unassisted through the mud trackway at Kilham Bear Center in Lyme, New Hampshire. Credit: Video by Jeremy DeSilva

Based on footprints collected from semi-wild chimpanzees at Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Uganda and two captive juveniles at Stony Brook University, the team found that chimpanzees have relatively narrow heels compared to their forefoot, a trait shared in common with bears. But the Laetoli footprints, including those at Site A, have wide heels relative to their forefoot.

The Site A footprints also contained the impressions of a large hallux (big toe) and smaller second digit. The size difference between the two digits was similar to humans and chimpanzees, but not black bears. These details further demonstrate that the footprints were likely made by a hominin moving on two legs. But in comparing the Laetoli footprints at Site A and the inferred foot proportions, morphology, and likely gait, the results reveal that the Site A footprints are distinct from those of Australopithecus afarensis at Sites G and S.

“Through this research, we now have conclusive evidence from the Site A footprints that there were different hominin species walking bipedally on this landscape but in different ways on different feet,” says DeSilva, who focuses on the origins and evolution of human walking. “We’ve had this evidence since the 1970s. It just took the rediscovery of these wonderful footprints and a more detailed analysis to get us here.”

Reference: “Footprint evidence of early hominin locomotor diversity at Laetoli, Tanzania” by Ellison J. McNutt, Kevin G. Hatala, Catherine Miller, James Adams, Jesse Casana, Andrew S. Deane, Nathaniel J. Dominy, Kallisti Fabian, Luke D. Fannin, Stephen Gaughan, Simone V. Gill, Josephat Gurtu, Ellie Gustafson, Austin C. Hill, Camille Johnson, Said Kallindo, Benjamin Kilham, Phoebe Kilham, Elizabeth Kim, Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce, Blaine Maley, Anjali Prabhat, John Reader, Shirley Rubin, Nathan E. Thompson, Rebeca Thornburg, Erin Marie Williams-Hatala, Brian Zimmer, Charles M. Musiba and Jeremy M. DeSilva, 1 December 2021, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-04187-7

The other co-authors include: Catherine Miller, James Adams, Jesse Casana, Nathaniel Dominy, Luke Fannin, Stephen Gaughan, Austin C. Hill, and alumni Camille Johnson ’19 and Anjali Prabhat ’20 at Dartmouth; Kevin G. Hatala and Erin Marie Williams-Hatala at Chatham University; Andrew S. Deane at Indiana University School of Medicine; Kallisti Fabian, Josephat Gurtu and Said Kallindo at the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority; Ellie Gustafson and Rebeca Thornburg at University of Colorado Denver; Simone V. Gill at Boston University; Elizabeth Kim at the University of Southern California; Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce and Brian Zimmer at Appalachian State University; Blaine Maley at Idaho College of Osteopathic Medicine; John Reader at University College London; Shirley Rubin at Napa Valley College; and Nathan Thompson at NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine.