Scientists say they’ve found striking evidence that a common infection caused by the Epstein-Barr virus is the leading cause of multiple sclerosis. Their research has found that military personnel who newly tested positive for the virus went on to have a substantially higher risk of later developing multiple sclerosis than those who didn’t. The findings seem to support the need for a preventative vaccine or treatments that can directly target the typically lifelong latent infection.

Multiple sclerosis is a rare but debilitating neurological disorder that is thought to affect about 1 million people in the U.S. Those with multiple sclerosis have an overzealous immune system that eats away at the protective coating of our nervous system, known as myelin. Over time, the lack of myelin slows down and damages the connections between our brain and body, leading to a range of symptoms like numbness, muscle weakness, pain, and difficulty walking.

Multiple sclerosis progresses differently from person to person following the initial flare-up, and most people at first will avoid symptoms and clear neurological damage for months or years at a time between relapses. But about 10% to 20% of multiple sclerosis sufferers have to live with constant and often worsening symptoms, while some with the relapsing form of multiple sclerosis will eventually stop having periods of remission. In the most severe cases, people lose their ability to write, speak, and walk, and even the average sufferer has a shorter life expectancy.

There is no clear established cause of MS, though it’s long been suspected that certain viral infections may be the initial trigger for many cases. And one of the most prominent suspects has been the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

EBV is a herpesvirus that’s contracted by nearly everyone at some point in their lives. The infection usually doesn’t make kids sick, but when caught during the teen or adult years, it’s one of the major causes of infectious mononucleosis, or mono—an acute illness that causes fatigue, fever, and sometimes rash for about two to six weeks. Following the initial illness, though, the virus then lays dormant in our body and usually doesn’t cause visible trouble again, though it can do so in people with weakened immune systems.

Some evidence has suggested a link between EBV and multiple sclerosis, which has included finding traces of EBV in the lesions caused by the disorder. But one major stumbling block to establishing a clear cause-and-effect relationship between the two is that, because EBV is so common, it can be hard to find people before they get infected and track them over time to see if they develop MS, and to compare their risk to people who don’t catch the virus. This new research, published Thursday in Science, seems to have accomplished just that.

The research team, led by scientists at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, was able to track the long-term health of about 10 million active duty military members, thanks to a 20-year collaboration with the U.S. military. At the start of their service, these members have their blood screened for HIV and are screened regularly every two years afterward. This meant the researchers could test those same blood samples for EBV as well.

Over the 20-year study period, 955 individuals were diagnosed with multiple sclerosis during their service. Out of the 801 MS cases who had testable blood samples, only one didn’t test positive for EBV antibodies. The team also looked at thirty-five people who later developed multiple sclerosis but who were negative for EBV at the start of their military service, and they were compared to controls who also tested negative for the virus and didn’t develop multiple sclerosis. All but one of those people contracted the virus before their eventual MS diagnosis. By contrast, people in the control group who never developed MS were also less likely to have caught EBV during the study period.

According to study author Marianna Cortese, the associated risk of developing MS was 32-fold higher in those who contracted the virus than in those who avoided infection—a difference so high that it would be incredibly unlikely for that to be a mere coincidence and one that “provides compelling evidence of causality,” she said in an email.

“A risk of this magnitude is unusual in scientific research. The strength of this result and other aspects of the study and findings indicate that this cannot be explained by other risk factors and makes us confident that EBV is the leading cause of MS,” Cortese added.

Using the same blood samples, Cortese and her team were also able to look for the presence of markers associated with neuroaxonal degeneration, a sign of MS that can appear long before symptoms do. And again, they found that these markers in MS sufferers initially negative for EBV were showing up only after the virus had infected them, lending more support to a causative link. They also failed to find any similar link between MS and human cytomegalovirus, another very common herpesvirus, further suggesting that there really is something crucial about the role EBV plays in multiple sclerosis.

Because EBV is so common, yet multiple sclerosis is so rare, there are likely other important factors that influence someone’s risk, including genetics. There was also one case of MS found in someone without a prior EBV infection, which could mean that other infections are a less common trigger. But the study’s findings, assuming they are validated by other research, have some important implications for how we handle EBV moving forward.

“If EBV is the leading cause of MS, then the disease could be prevented by preventing EBV infection, for example with a vaccine,” Cortese noted. “Further, targeting the virus with EBV-specific drugs could lead to better treatment for the disease.”

It wouldn’t be the first vaccine developed for a germ to prevent a separate but linked condition down the road. The HPV vaccine is already starting to prevent many cases of cervical cancer in the first women who received it.

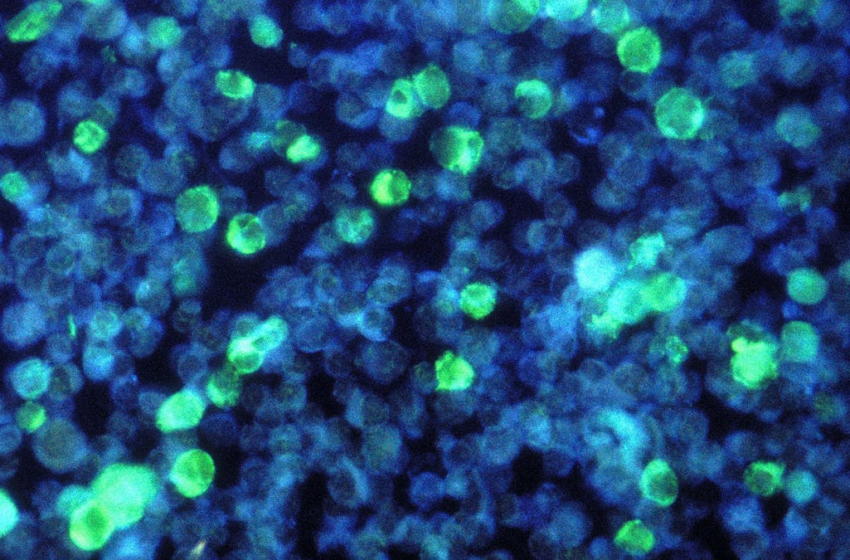

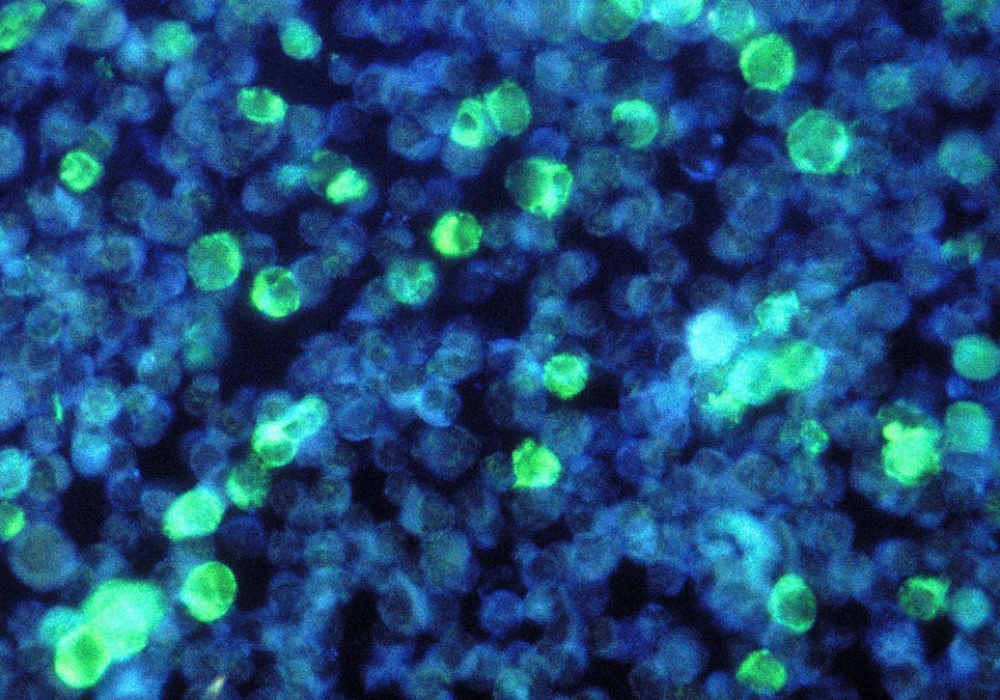

There’s also some evidence that latent EBV infections may affect the course of MS symptoms. Currently, one of the most effective treatments for multiple sclerosis is anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, which deplete the body’s supply of circulating memory B cells that can attack the nervous system. But these cells are also where EBV hides, so it’s possible that some of the benefits of these drugs may come from getting rid of EBV. And if that’s the case, then developing antivirals that can directly target EBV may be a better strategy than these antibodies, which have to be administered intravenously and weaken the immune system.