NASA is about to launch the world’s most powerful space telescope. Webb’s first year of science could rewrite the history of the universe.

NASA is about to open a never-before-seen window into the cosmos. Starting next year, astronomers should be able to peer into the atmospheres of planets orbiting distant stars, analyze the aftermath of the universe’s most violent collisions, and look further back in time than ever before.

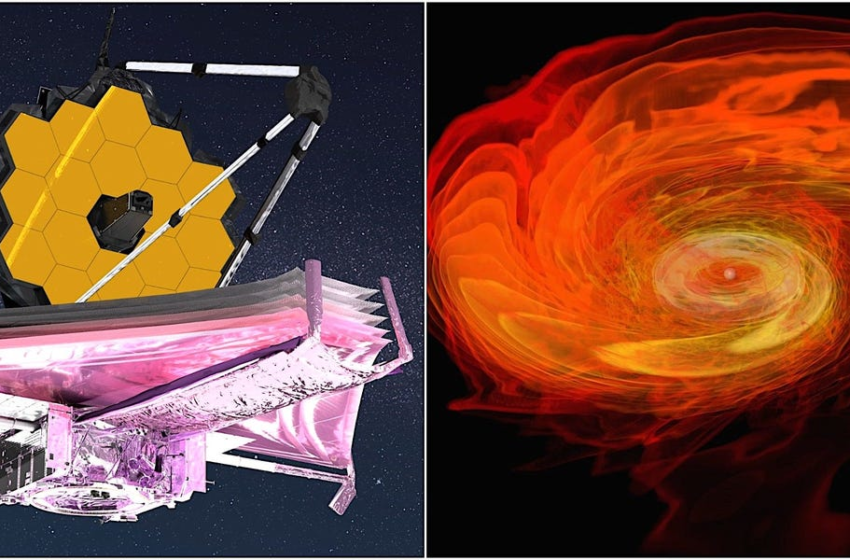

That’s because the James Webb Space Telescope — JWST, or simply “Webb,” for short — is folded up, full of fuel, and waiting to be loaded onto a rocket in French Guiana.

NASA’s last game-changing space observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, launched in 1990. It, too, was on a mission to document the 13.8-billion-year history of the universe.

Hubble is still observing the cosmos, and NASA hopes to keep using it for a few more years, possibly into the 2030s. But Hubble could only see so far, and Webb is designed to see even farther.

In collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency, NASA has spent decades and more than $10 billion building Webb, which is set to launch into space on December 22. While Webb was first conceived of in the 1990s and originally slated to cost $500 million, a redesign and delays both drove up its price tag and pushed back its launch date.

After launch, if all goes according to plan, Webb will spend six months unfolding and adjusting itself, falling into an orbit 1 million miles from Earth. Then it can begin rewriting cosmic history.

The telescope’s main project is to investigate how galaxies formed and grew after the Big Bang — peering into the universe’s depths to capture images of the first galaxies ever formed. Its infrared cameras are so powerful and precise that they could spot a bumblebee 240,000 miles away — the distance between Earth and the moon.

Webb will also help astronomers investigate mysteries they hadn’t considered when NASA first designed the telescope.

“Webb has this broad power to reveal the unexpected. We can plan what we think we’re going to see, but at the end of the day, we know that nature will surprise us more often than not,” Klaus Pontoppidan, a Webb scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, said in a press briefing on November 18.

NASA expects the telescope to probe the secrets of the cosmos for at least a decade. Even the telescope’s first year in space is jam-packed, with nearly 400 investigations from thousands of scientists all over the world, Pontoppidan said.

From peering at Mars to investigating ancient galaxies, here are a few of the most exciting projects that Webb — the most powerful space telescope ever built — is expected to tackle in its first year:

Light from the first galaxies is still traveling to Earth, and Webb may spot it

As a telescope peers into the distance, it’s also looking back in time. That’s because it takes time for light to travel. When you look at the sun — please, don’t! — you’re seeing light that our star emitted eight minutes ago. When Hubble looks at distant galaxies, it’s seeing light from billions of years ago, as far back as 400 million years after the Big Bang.

“We have this 13.8-billion-year story — the universe — and we’re missing sort of a few key paragraphs in the very first chapter of the story,” Amber Straughn, a scientist on NASA’s Webb team, said in the November 18 briefing. “JWST was designed to help us find those first galaxies.”

Webb is expected to spot galaxies that formed when the universe was just 100 million years old.

It’s 100 times more powerful than Hubble. It’s also using infrared light, which has wavelengths that can cut through dust clouds that may have obscured Hubble’s view, which relied on visible light.

Webb should see deeper into the cosmos and detect galaxies — the first ones formed after the Big Bang — that are too distant and faint for Hubble to pick up.

Looking for gold forged by the universe’s most violent collisions

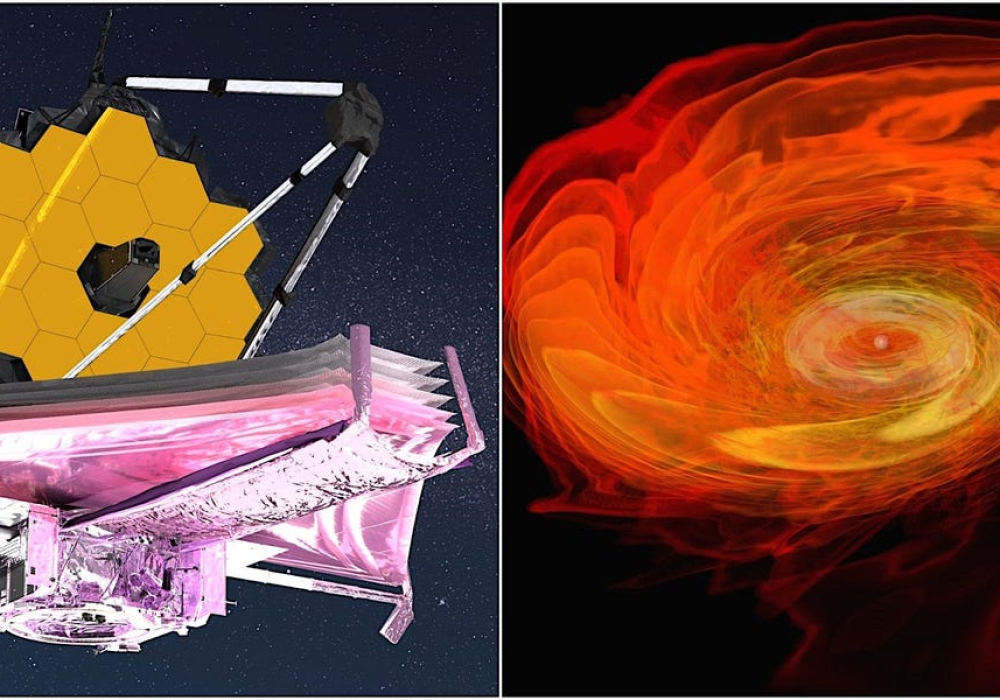

For the last six years, gravitational-wave detectors on Earth have been sensing ripples in space-time created by the most violent events in the cosmos: black holes and neutron stars crashing into one another.

Scientists think these collisions forged most of the universe’s heavy elements, like silver, gold, and platinum. Webb will try to confirm that by focusing on distant collisions of neutron stars — the dense cores of stars that have collapsed, ejected their outer layers, and died.

Webb will be able to analyze the entire spectrum of infrared light from those collisions. That will allow astronomers to indentify individual elements like gold or platinum in the explosion debris, based on their wavelengths of light.

This method, called spectroscopy, will help astronomers learn about other objects Webb studies, too.

“Spectra will be the bulk of the science,” Antonella Nota, a Webb scientist who leads the ESA office at the Space Telescope Science Institute, said in the briefing. “While an image, we say is worth 1,000 words, spectra for astronomers are just worth 1,000 images.”

Our first glimpse at the atmospheres of planets that could host life

When it’s not busy studying the most massive objects and ancient galaxies in the universe, Webb will search for less extreme environments, worlds where conditions could be just right to give rise to life.

Exoplanets — worlds orbiting other stars — were barely a field of study when NASA began designing Webb. Two decades later, astronomers have identified dozens of exoplanets that could be temperate enough for alien life. They’re not too cold, not too hot, just right for water — but only if they have hospitable atmospheres.

Webb will watch potentially habitable exoplanets pass in front of their stars, and analyze the spectra of starlight that shines through the planets’ atmospheres. That spectroscopy will indicate to scientists whether the air on other worlds contains compounds that could point to life, like carbon dioxide, methane, or water.

“This telescope is definitely our next big step in our search for potentially habitable planets,” Straughn said.

These aren’t necessarily Earth-like planets. Stars like the sun are so big and bright that Webb wouldn’t be able to see the tiny Earth-like planets orbiting them. That’s a job for the next great space telescope. Instead, Webb will look at rock planets orbiting stars that are much smaller and dimmer.

Some of its first targets will be planets circling a small star, TRAPPIST-1, just 39 light-years away.

The star has seven rocky planets, three of them in its “Goldilocks zone,” meaning they’re just the right distance to have temperatures that would allow liquid water to exist on their surfaces.

Webb is also set to zoom in on uninhabitable, but fascinatingly extreme, planets. At least one of the planets on its roster is so close to its star that its surface is molten, and it may even rain lava there. Webb should be able to detect that lava rain.

The telescope will also examine every object in our solar system, starting with Mars and working its way outward to the icy objects beyond Pluto.

In those planets, stars, and galaxies, near and far, Webb is sure to uncover major surprises.

“Webb will probably also reveal new questions for future generations of scientists to answer — some of whom may not even be born yet,” Pontoppidan said.