It’s the foundational concept of US democracy: voters choose the politicians they want to represent them.

Yet the reality in 2021 is much more depressing. As politicians undertake the once-a-decade process of redrawing political districts across the country, they are essentially rigging the system by deciding among themselves exactly which voters in which areas they want to represent. It’s a process called gerrymandering that allows them to virtually choose their voters and guarantee their re-election.

The United States stands almost alone in allowing partisan politicians to draw political districts in this way. It’s an invisible scalpel that profoundly affects US politics but also the tenor and character of the national discourse.

Republicans have control of the process in many states this year. And so far, they’re maximizing their advantage wherever they can. The new lines will likely help Republicans retake control of the US House next year.

Let us show you how the Republicans are gerrymandering in four important parts of the country.

Dismantling a Democratic district

In North Carolina, Republicans have drawn a new congressional map that gives them a lock on at least 10 of the state’s 14 congressional seats. That’s a staggering advantage in a state that re-elected a Democratic governor in 2020 and where Joe Biden got 48.6% of the statewide vote.

Remarkably enough, federal courts can’t do anything to stop this kind of extreme gerrymandering on partisan grounds, the supreme court ruled in 2019.

There are few limits on the process. Each district must have roughly the same number of people. In many places they must be reasonably compact. And lawmakers can’t dilute the influence of voters based on their race.

But politicians are free to group voters based on their partisan leanings. And in recent decades, they’ve done that surgically, carving up communities to essentially lock in advantages for years to come. A decade ago, Republicans launched a hugely successful effort, called Project REDMAP, to take control of state legislatures and then used their new majorities to draw maps that locked in their advantage for a decade. This year, Republicans have the power to draw the lines of 187 congressional districts while Democrats have power in 75, according to the Cook Political Report.

During the 2012, 2014 and 2016 midterm elections, gerrymandering shifted 59 congressional seats, 39 for Republicans and 20 for Democrats, according to a report from the left-leaning Center for American Progress.

While Democrats have gerrymandering power in far fewer places this year, they’ve also shown a willingness to use their scalpel where they have control in places such as Illinois and Oregon.

Diluting the influence of Black voters

Although it is illegal to carve up districts that weaken the influence of voters based on their race, sometimes lawmakers do it anyway.

Weakening diverse, Democratic-leaning suburbs

In Texas, Republicans have drawn lines that blunt the immense growth among the Democratic-leaning Hispanic population to shore up the GOP’s hold on as many as 25 of the state’s 38 congressional seats.

Even though people of color accounted for 95% of the population growth over the last decade, there are no districts where minorities make up a majority of the population.

Until 2013, states with a history of voting discrimination, including Texas, had to get their maps pre-cleared by the federal government before they went into effect to ensure they didn’t discriminate against minority voters. Now, Texas has much more leeway to pass maps that discriminate against people of color.

Packing Democrats into non-competitive districts

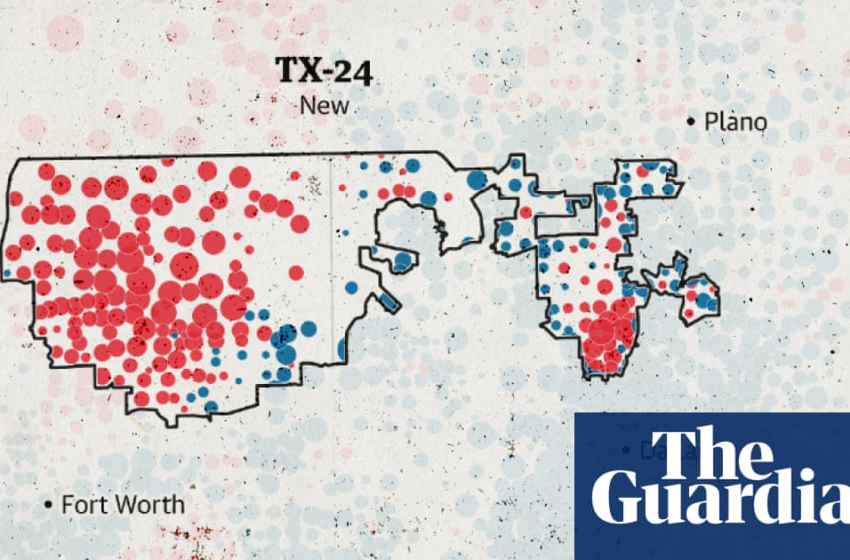

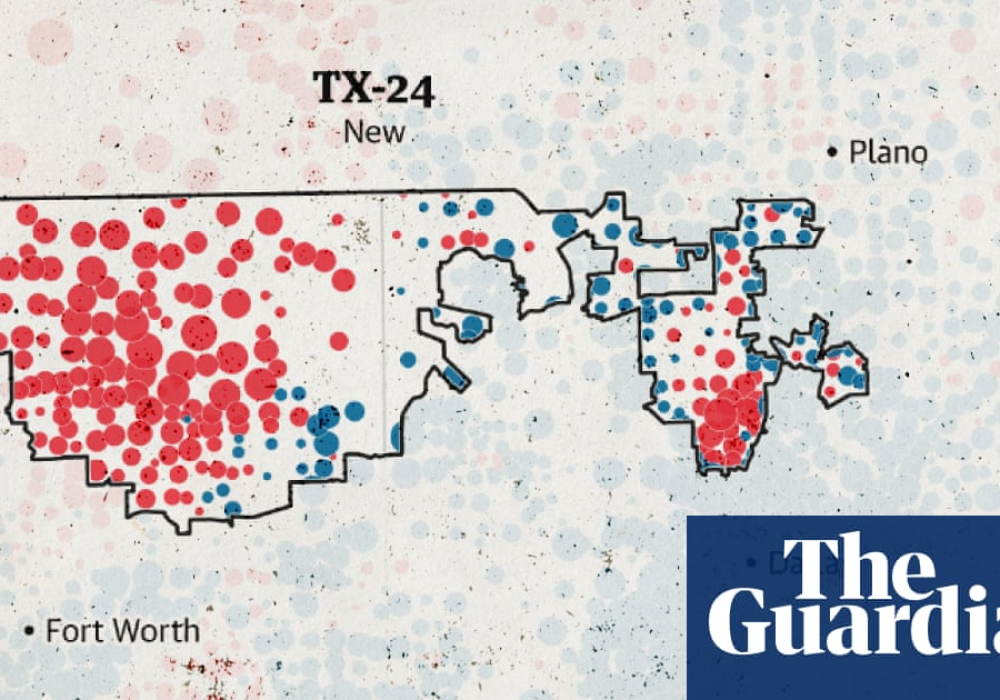

The Dallas-Fort Worth area in Texas is one of the fastest growing areas in the state – and one of the most politically competitive. Because each district must have roughly the same number of people by law, Texas Republicans had to get creative in how they regrouped voters.

In some places, they took small slivers of heavily populated Democratic suburbs and attached them to rural GOP areas. In other cases, they excised Democrats from politically competitive districts and packed them into districts that already favored Democrats.

Voting rights advocates face an uphill battle in challenging these maps in court. In 2019, the US supreme court said there was nothing federal courts could do to stop partisan gerrymandering.

Redistricting litigation often takes years to move its way through the court, allowing lawmakers to get at least one election, and often many more, conducted under district lines that may later get struck down.

In the meantime, the effects are insidious. When politicians know their seat is safe, they no longer have to worry about competition from the opposing party or concern themselves with reaching out to the other party’s voters.

Instead, they become more interested in appealing to their own base and fending off challengers from within their own party. It makes politics more extreme, and contributes to extreme polarization.