The sample arrived in Dr. Charles Chiu’s UCSF lab around 6 p.m. Tuesday, tucked into a high-tech cooler too small to hold a six-pack of beer.

Already, Chiu and his team knew the sample — which contained viral material extracted from a nasal swab — came from a San Francisco resident who had tested positive for the coronavirus and recently returned from South Africa. There was a fair chance that in their hands was the first known case of omicron in the United States.

And after spending the night in the lab, watching the results of genetic testing on the sample spool out hour by hour, they would have confirmation before sunrise.

“I did get some pushback from my lab — ‘Are you sure it’s the real thing? Should we really spend our whole night working on this?’” Chiu said with a laugh at noon Wednesday, just after a City Hall news briefing announcing the discovery of omicron. He said he had slept “a little” the night before, but he had been alert since 4 a.m. at least, when the final results came in and he contacted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to officially report the case.

That the first U.S. case of omicron — the highly mutated coronavirus variant drawing global concern as potentially the next major threat in the pandemic — was identified in San Francisco may simply have been a matter of geography: The Bay Area is a hub of international traffic, and omicron, as expected, was found first in a traveler from the region where the variant emerged.

But the rapid discovery, made less than 48 hours after the person tested positive for the virus, was aided by a savvy patient who self-reported the case along with travel history, public health officials who quickly corralled the sample to send to Chiu, and a small team of UCSF scientists who worked through the night to produce the genomic sequence that would confirm it was indeed omicron.

“We knew it would be here. We didn’t know San Francisco would be the first,” said Dr. Susan Philip, the San Francisco health officer. “It was a really great collaboration to get this result as quickly as we did. It was a combination of this person being very well informed and contributing to the greater good, and having someplace to receive that information, and having the expert staff and colleagues to run the tests.”

At least one more suspected U.S. case of omicron was detected on Thursday, the day after San Francisco’s case — in a person from Minnesota who developed mild symptoms shortly after attending an anime convention in New York City.

The San Francisco resident is not being identified. Health officials said the person, who reported mild symptoms, had been fully vaccinated with two doses of Moderna but had not received a booster.

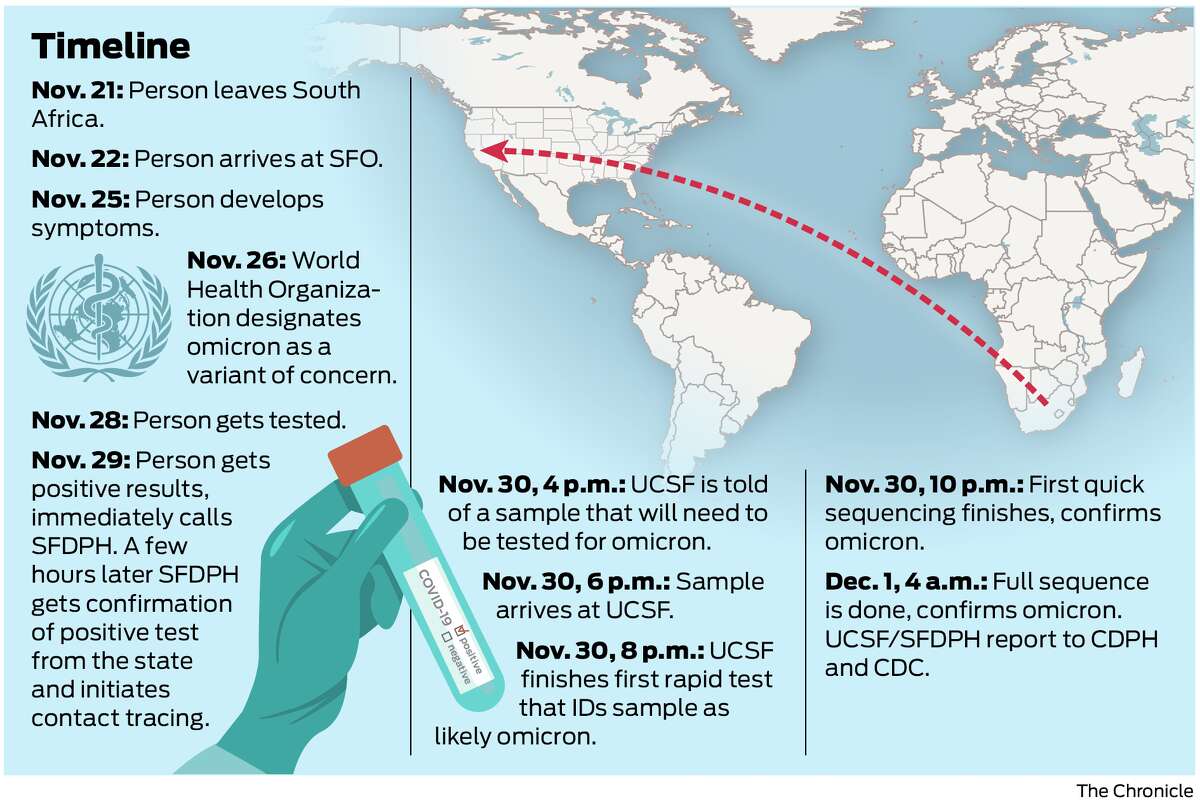

The person left South Africa on Nov. 21, Philip said, and arrived at San Francisco International Airport the next day. Symptoms began three days later, on Thanksgiving — the same day the first case of omicron was announced in South Africa, though the variant is now believed to have surfaced at least a month earlier. The San Francisco resident got tested for COVID the following Sunday, Nov. 28.

When the results came back positive on Monday, the person immediately called the public health department, Philip said. “The individual pieced together, ‘Hey, I’ve been traveling to South Africa.’ They proactively reached out to us,” Philip said. “Their calling happened before the result made its way through the usual process to us.”

Typically, positive tests take a few hours to get from the lab that produces results to the local public health department — they’re funneled first through the state, which ensures that counties get results based on where residents live and not necessarily where they took the test.

In this case, once San Francisco officials got the official state results, they contacted the person again and began collecting more details about the travel history, when the person became sick and with whom he or she had been in contact. That contact tracing is ongoing, but as of Wednesday no close contacts are known to have tested positive.

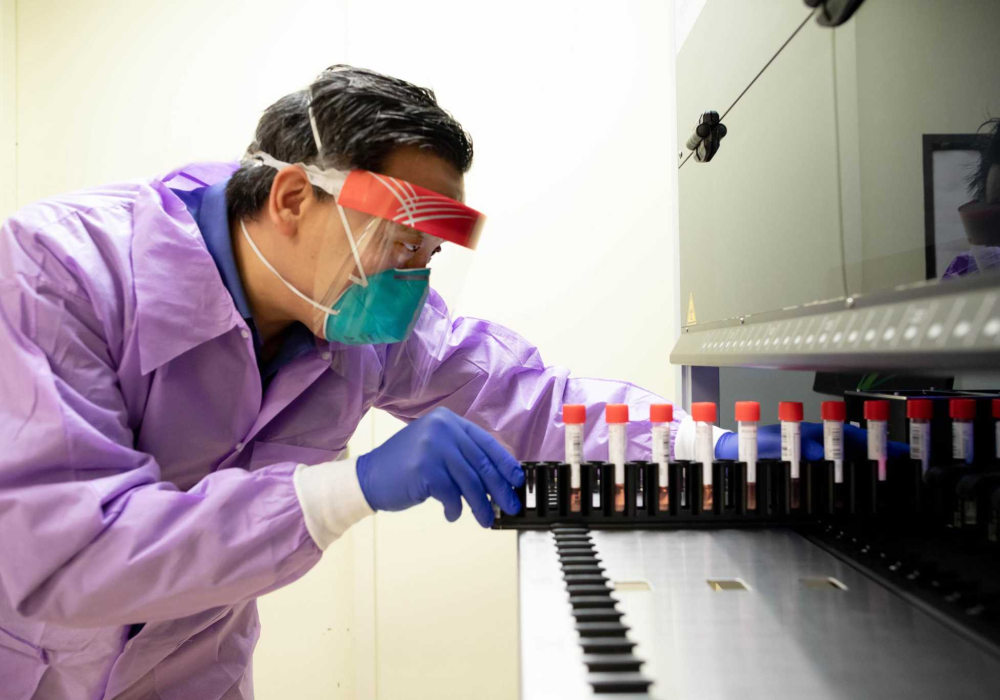

Public health officials contacted Chiu around 3 p.m. Tuesday to ask if his lab could perform a simple test that would tell them quickly if it was probably omicron. He agreed, and the next step was having Color, the laboratory that performed the diagnostic test, track down the patient’s sample. By 5 p.m., Scott Topper, vice president of clinical operations for Color, was driving the sample from a facility in Burlingame to Chiu’s lab in Mission Bay.

The sample arrived on a PCR plate — a palm-sized square pocked with 96 tiny wells, each of which can contain extracted RNA. Because RNA easily degrades when it’s too warm, the sample had to be transported in the special cooler, which laboratory scientist Venice Servellita took over from Topper.

Servellita immediately set about running the initial test, which looks for three gene targets in the sample. With omicron, one of those three targets can’t be detected due to its many mutations; the result is known as an S-gene dropout. The alpha variant similarly shows up as an S-gene dropout, but alpha currently makes up “less than 0.1% of cases” in the U.S., Chiu said. If his team saw the dropout, that almost certainly meant they were looking at omicron.

As Servellita watched the testing results in real time, it quickly became obvious that two of the target genes were showing up, and one was not. “So clearly that’s a dropout,” Servellita said. “I was already preparing myself. I thought I’d better prepare an email template to tell everyone right away.”

Even as Servellita awaited the first results, her colleague Yueyuan Zhang, a postdoc in Chiu’s lab, was getting ready to start genomic sequencing. Once she had prepped her own sample and had the equipment set up, she took a nap in the staff lunchroom — it was only about 7 p.m., but it was going to be a long night.

Servellita had her results about 90 minutes after the sample had arrived at the lab, and she emailed a group thread that included Chiu and officials with San Francisco public health. Between the S-gene dropout and the patient’s travel history, everyone now knew that they had omicron, but they still needed the genomic sequencing to confirm it.

Zhang began the sequencing around 8 p.m., using a machine that is less efficient than the equipment most labs use to analyze dozens of samples at once but produces results much faster. Typically, sequencing can take a full day or two — in this case, they were hoping for hours.

The sequencer produces results as it runs, so scientists can collect and analyze the data along the way. By 10 p.m., Chiu thought they had roughly half of the genome.

“I believe there are about 46 mutations total in omicron — this is a crazy variant — and with half of the genome, we’d found about half of the mutations,” Chiu said. “So it couldn’t be really anything else at that point.”

Chiu contacted local public health officials with the preliminary results, but they had to keep sequencing, to collect as much of the genome as possible. Zhang stayed up all night with the machine. She doesn’t typically babysit sequencing, but omicron with its many mutations is a tricky variant, and she didn’t want the results to be murky because some part of the process failed.

They had the bulk of the genome by 2 a.m., which was when Chiu contacted Servellita — who had gone home just before midnight — and asked her to help him assemble and analyze the data, a job she could at least do from her living room. By 4 a.m., Chiu and the team felt confident that they had indeed confirmed omicron through sequencing, and he contacted the CDC.

Philip, who had been up until almost midnight coordinating the public health response if the case turned out to be omicron, learned of the sequencing results around 5:30 a.m., which is when she usually gets up anyway. Her team began working on how they would communicate the news to the public.

Word was already leaking to some of Chiu’s colleagues, though. By noon he’d had a dozen requests for access to the RNA sample so scientists could begin studying the variant. He asked Servellita to return to the lab around 9 a.m. to start getting the samples ready to share.

And Zhang finally went home just after sunrise.

“It feels kind of like magic and luck, how this happened,” Zhang said Wednesday evening, after she’d had a few hours to reflect on the work. “I knew omicron would come to the U.S., and I knew one day people would find it. But I never thought it would come from us.”

Chronicle staff writer Catherine Ho contributed to this report.

Erin Allday is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: eallday@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @erinallday