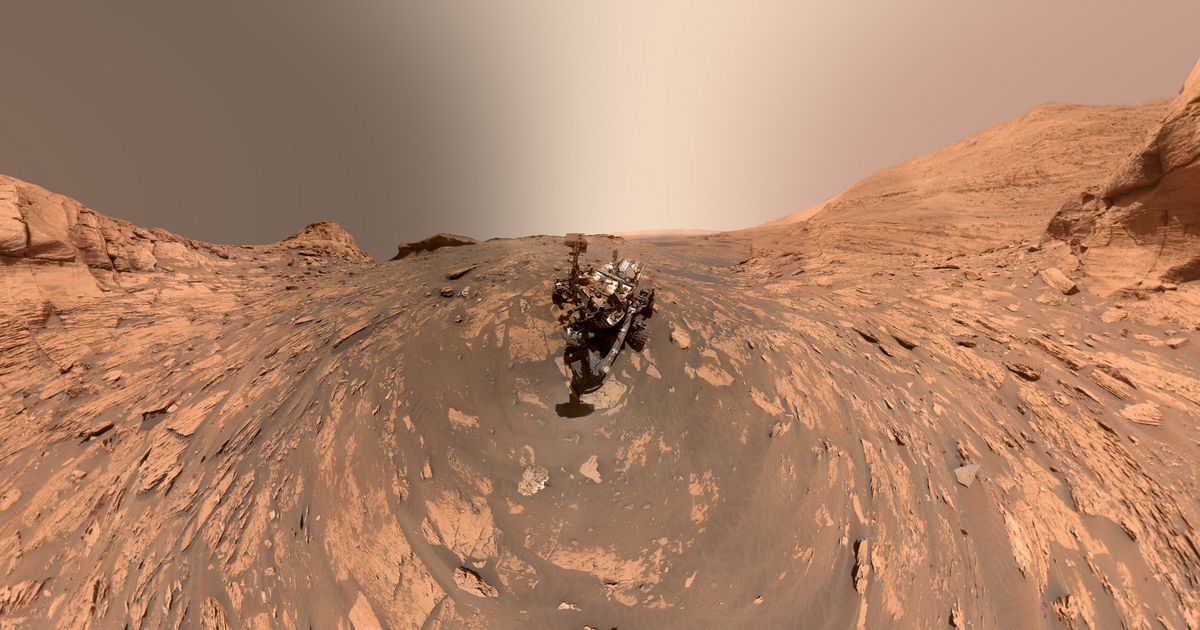

NASA’s Curiosity rover captured this selfie in late 2020.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill

This story is part of Welcome to Mars, our series exploring the red planet.

When the words “intriguing,” “Mars” and “ancient life” show up in the same NASA statement, my ears perk up. On Sunday, NASA talked up a new study looking at “unusual carbon signals” measured by the Curiosity rover in the red planet’s Gale Crater.

Curiosity hasn’t found proof of ancient microbial life on Mars, but scientists aren’t ruling it out as one possible explanation for the rover’s findings. Powdered rock samples studied by the rover show the kind of carbon signatures that are connected to biological life on Earth. But Mars may be telling a very different story.

The study is set to be published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal.

From the lab to your inbox. Get the latest science stories from CNET every week.

Carbon is a key element in life on our own planet, so it’s important to study how it appears on Mars. “For instance, living creatures on Earth use the smaller, lighter carbon 12 atom to metabolize food or for photosynthesis versus the heavier carbon 13 atom,” NASA said. “Thus, significantly more carbon 12 than carbon 13 in ancient rocks, along with other evidence, suggests to scientists they’re looking at signatures of life-related chemistry.”

NASA’s Curiosity rover made this drill hole in the Gale Crater on Mars. Scientists found intriguing carbon signatures in some samples the rover has studied.

NASA/Caltech-JPL/MSSS

Curiosity heated up rock samples in an onboard lab and used its Tunable Laser Spectrometer instrument to measure the gases released by the samples. Some of the rock samples had “surprisingly large amounts of carbon 12” compared with what has been found in the atmosphere of Mars and in Martian meteorites.

According to a statement from Penn State, the researchers proposed several explanations: “a cosmic dust cloud, ultraviolet radiation breaking down carbon dioxide, or ultraviolet degradation of biologically created methane.”

The cloud idea connects back to an occurrence when the solar system passed through a galactic dust cloud hundreds of millions of years ago, which could have left carbon-rich deposits on Mars. The second idea suggests ultraviolet light could have interacted with carbon dioxide gas in the Martian atmosphere and left molecules with the distinctive carbon signature on the surface.

A biological origin idea could have involved bacteria releasing methane into the atmosphere that was then converted into molecules that settled back down on Mars, leaving behind the carbon signature Curiosity found.

Mars and Earth have experienced very different lives, so scientists are wary of applying Earth expectations to Mars data. “All three possibilities point to an unusual carbon cycle unlike anything on Earth today,” said Penn State geoscientist Christopher House, who led the study. “But we need more data to figure out which of these is the correct explanation.”

Curiosity has been on Mars since 2012 and is continuing to examine rocks and sediment as it travels around the crater. Its study of carbon isotopes may not yet be able to answer the question of whether the red planet once hosted life, but the investigation continues.