Dirley Cortés, a doctoral candidate in the Redpath Museum at McGill University in Montreal, reanalyzed the fossil and uncovered it had been wrongly categorized. The meter-long skull dates back 130 million to 115 million years, during the Cretaceous period, according to Cortés. This time frame comes after the global extinction event at the end of the Jurassic period, she said.

Colombia was an “ancient biodiversity hotspot,” Cortés said, so fossils like this freshly identified marine reptile act as puzzle pieces to understanding the evolution of marine ecosystems.

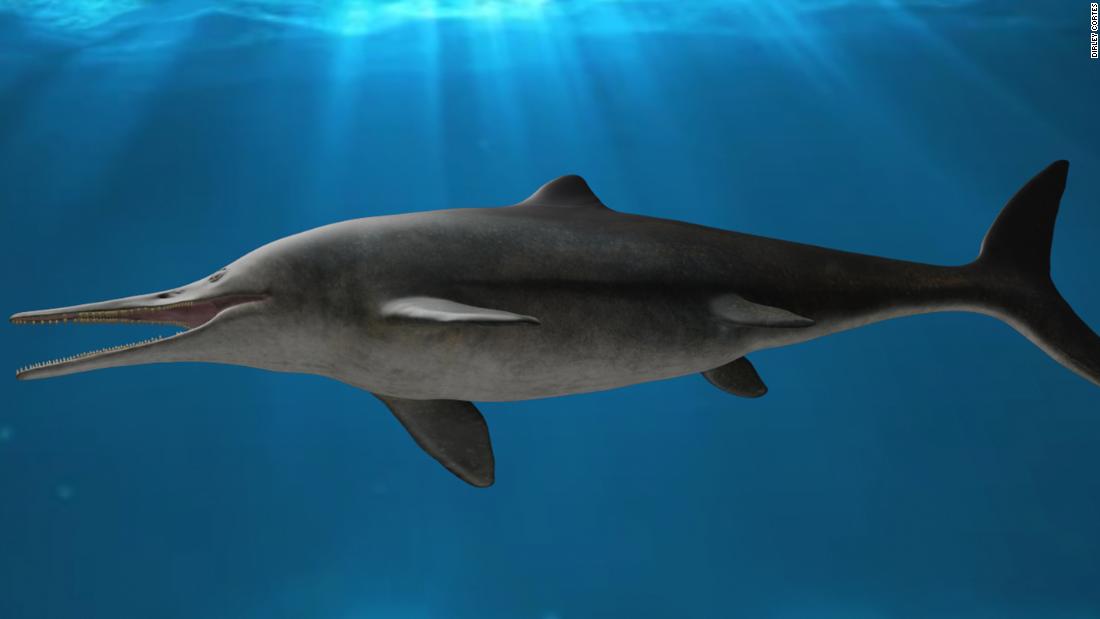

Other ichthyosaurs have small, equally sized teeth perfect for eating small prey, Cortés said. In contrast, the teeth on the skull specimen have “modified its tooth sizes and spacing to build an arsenal of teeth” for catching bigger prey, she said.

The teeth would make it easier for the sizable predator to capture, puncture, saw and crush large prey, she explained. Some of its meals could have included other marine reptiles and big fish, Cortés added.

The carnivorous creature had an elongated snout and would have been about 4 to 5 meters long (13.1 to 16.4 feet), she said. The animal could open its jaw around 70 to 75 degrees, Cortés said, making it easier to eat larger animals.

The species was labeled Kyhytysuka sachicarum, which means “the one that cuts with something sharp from Sáchica” in the ancient language of the Indigenous Muisca people in Colombia. Sáchica is a town near Villa de Leyva, where the partial skull was found.

Understanding marine ecosystems in transition

The research holds a special place in Cortés’ heart because the specimen was found where she grew up, she said.

“My PhD research has direct implications for paleontological development in Colombia and the Neotropics, a field that is still emerging compared to the history of developed countries, so it’s so rewarding to get to do research here too,” Cortés said via email.

After this discovery, Cortés said she’s turning her attention to analyzing fossils in the Centro de Investigaciones Paleontológicas of Villa de Leyva, Colombia.

“We’re discovering many new species there that are helping us understand the evolution of marine ecosystems during a transitional time,” Cortés said.

Following the global extinction event, the Earth was going through a cool period with rising sea levels, she said. The supercontinent Pangea was also separating into northern and southern landmasses, she added.