The Federal Reserve building is seen in Washington, U.S., October 20, 2021. REUTERS/Joshua Roberts/File Photo

WASHINGTON, Nov 11 (Reuters) – Inflation pushed more broadly through the economy in October again challenging the Federal Reserve’s outlook for only “transitory” price increases, offsetting recent wage hikes in a blow to consumers, and prompting investors to boost bets the central bank will raise interest rates sooner than expected.

Yields on two-year Treasury notes , a proxy for the outlook for the overnight interest rate set by the Fed, jumped 6 basis points, the most in three weeks and among the largest daily increases in the last year and a half, to 0.485% on Wednesday after the release of data showing consumer prices rose by 6.2% in October versus the year before.

That was the largest one-year jump in prices in 30 years and applied across staples like food, energy and rent, as well as to items like automobiles where the Fed has expected the pace of price increases to ease alongside pandemic-driven “bottlenecks” in global supply chains.

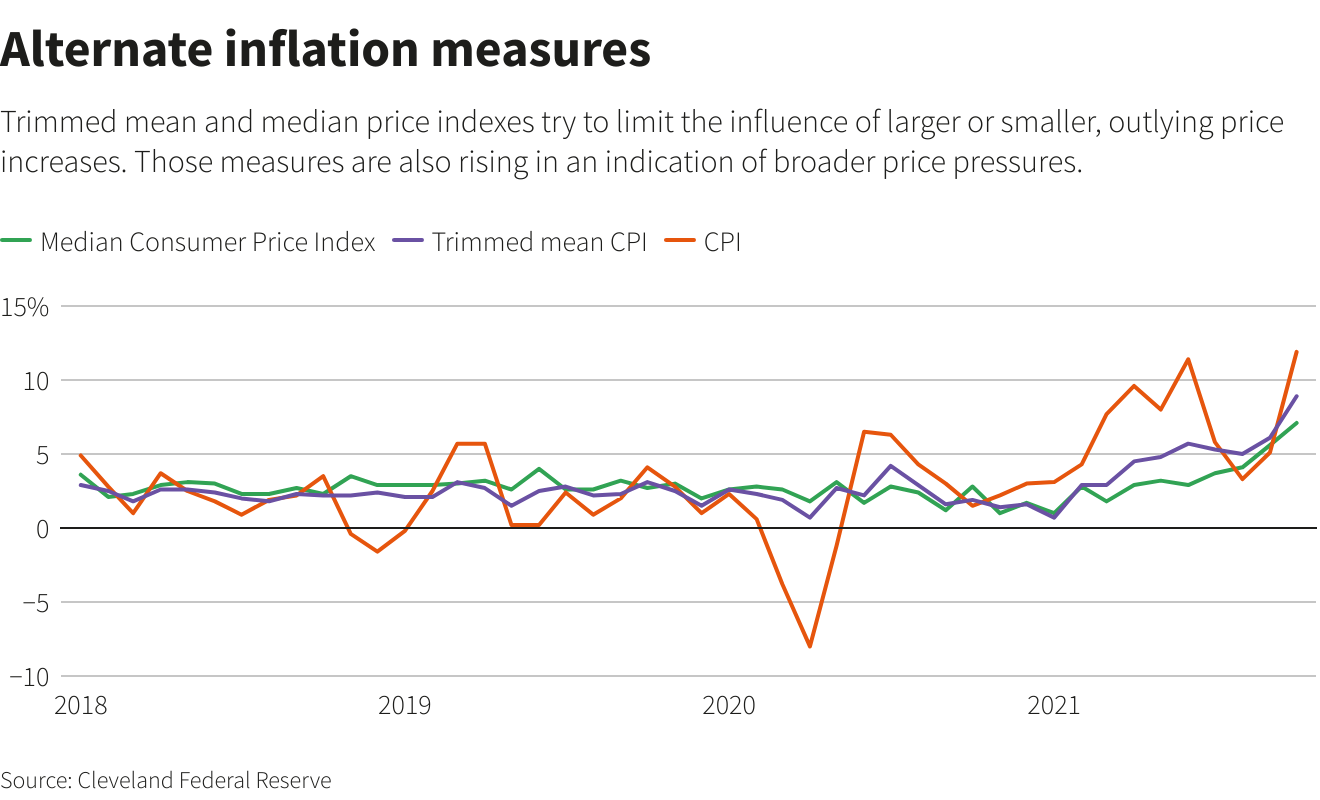

But those “bottlenecks” remain overrun by strong U.S. consumer demand, and inflation measures meant to diminish the impact of one-time spikes in goods and services are also rising.

Both a Cleveland Fed “trimmed mean” index of consumer prices and one that tracks the median level of price increases surged in a sign that price pressures were rising across a more extensive set of goods and services.

Still, one Fed policymaker on Wednesday said the central bank should still remain patient.

“We need to wait to see how this percolates through the economy,” before changing monetary policy in response to it, San Francisco Fed president Mary Daly said on Bloomberg TV .

Markets had a shorter leash. Pricing in futures contracts tied to the target federal funds rate showed investors boosting odds the Fed will by September raise rates twice by a cumulative 0.50 percentage point. Expectations for a third quarter-point rate increase in December increased to nearly 50% compared to less than 30% on Tuesday.

“The risks stemming from inflation have become increasingly top of mind to Federal Reserve policymakers, since excessive accommodation for too long, or essentially running the economy hot, could well hold unintended market consequences that further erode confidence and eventually impair the recovery,” said Rick Rieder, chief investment officer for global fixed income at investment giant Blackrock.

With demand, supply and wage pressures expected to continue, “near-term inflation readings may be intimidating to ‘inflation fighters’…which could press central bankers to at least discuss a faster reaction-function.”

NOT ‘LINEAR’

For both the Fed and the Biden administration, what was an adamant faith in transitory inflation has been tempered.

“We know that the recovery from the pandemic will not be linear,” Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers said on Twitter in a nod to prices rising still faster than anticipated. The CEA “will continue to monitor the data as they come in,” the office said.

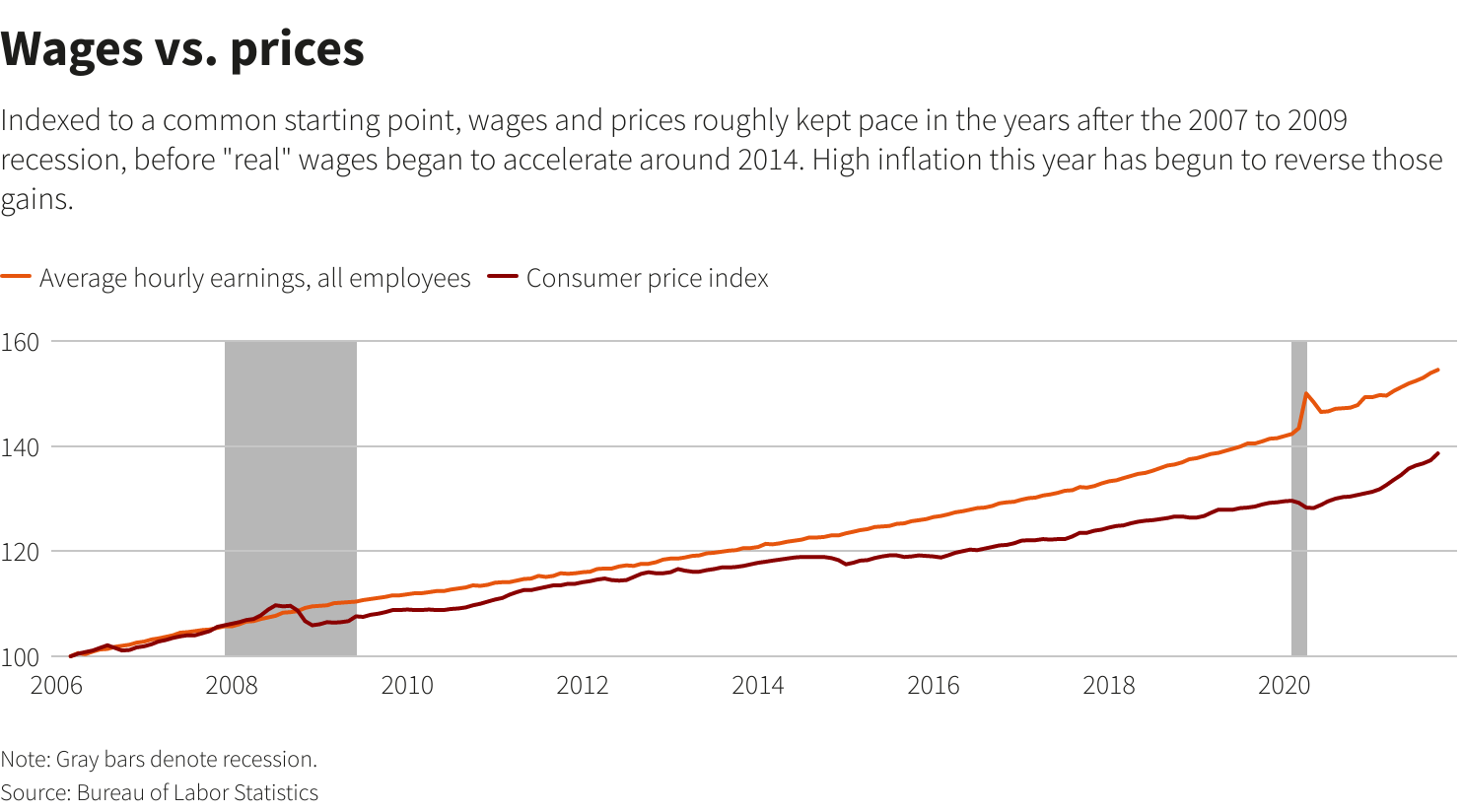

The price rises also have had the disconcerting effect of outpacing wage increases that the Fed and White House hoped would flow to lower-paid workers in the hotel, restaurant and other industries hardest hit during the pandemic shutdowns last year and the cautious return to in-person services since then.

On a month-to-month basis inflation almost fully offset the strong wage increases seen in the leisure and hospitality industry in October, noted Nick Bunker, research director for North America at job site Indeed.

Overall, real hourly wages fell 1.2% in October compared with the year before, with the nearly 5% wage gain of the past 12 months more than offset by the 6.2% rise in prices.

That continues reversing what had been a steady rise in workers’ purchasing power since around 2013, with the benefits of low inflation boosting “real” wages after several years of stagnation following the 2007-2009 financial crisis and recession.

The Fed has said it is reluctant to raise interest rates until more people have returned to jobs after being sidelined during the pandemic, even if inflation runs above its formal 2% target “for some time.”

The jobs-first strategy is a change from the previous approach which tried to use higher unemployment as a way to keep prices under control – in effect imposing the cost of inflation-fighting onto those rendered jobless during economic slowdowns.

The Fed still hopes inflation will ease, over time, without the need to ratchet interest rates higher to cool the economy, and risk slowing or reversing job growth in the process.

But the longer inflation data run beyond expectations, the tougher that will be.

“With annual inflation now topping 6%, is this sufficient to force the Fed’s hand? This long, long transitory period has to heap pressure on the Fed,” said Seema Shah, chief strategist at Principal Global Investors.

Reporting by Howard Schneider

Additional reporting by Ann Saphir in San Francisco and Shreyashi Sanyal in Bengaluru;

Editing by Dan Burns and Andrea Ricci

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.