Engineers activating the James Webb Space Telescope fine-tuned its electrical power system to better cope with the actual space environment and cooled down slightly warmer-than-expected motors before pressing ahead Monday with final deployment of the observatory’s critical sunshade.

Bill Ochs, the NASA project manager, said tightening up the sunshade’s five hair-thin layers, carefully pulling them taut with motor-driven cables running through multiple pulleys, likely would take three days to complete. But by Monday night, three of the five layers had been pulled into shape, with the final two awaiting tightening Tuesday.

The sunshade deployment has long been considered one of Webb’s most challenging hurdles, but “I don’t expect any drama,” Ochs said.

NASA

“I always tell folks, the best thing for operations is boring,” he said. “And that’s what we anticipate over the next three days. I think we’ll all breathe a sigh of relief once we get to the final layer five tensioning. But I don’t expect drama.”

Webb, the most expensive science probe ever built, was launched with great fanfare atop a European Space Agency-provided Ariane 5 rocket on Christmas Day, bound for an orbit around the sun a million miles from Earth.

Designed to capture infrared light from the first stars and galaxies to form in the wake of the Big Bang, Webb is extraordinarily complex. But other than minor growing pains common to all new spacecraft, Ochs said the $10 billion observatory is moving through its initial activation almost exactly as planned.

“We are still in the getting-to-know-you phase with the telescope,” he told reporters in a morning teleconference. “All satellites will always be a little bit different on orbit than they are on the ground, and it takes time to get to know that, understand their characteristics.

“That’s a lot of what we’ve been doing over the last week, as well as still making excellent progress on the commissioning timeline.”

The telescope’s solar array was deployed as planned moments after reaching space, two trajectory correction thruster firings were carried out, a high-gain antenna was unlimbered and pointed at Earth and two pallets holding the sunshade membranes were rotated into position.

An extendable tower lifted Webb’s primary mirror and instruments about four feet above the still-folded sunshade, providing clearance and additional isolation from the heat generated by the spacecraft’s electronics. A “momentum flap” then was deployed to counteract slight forces imparted by the solar wind.

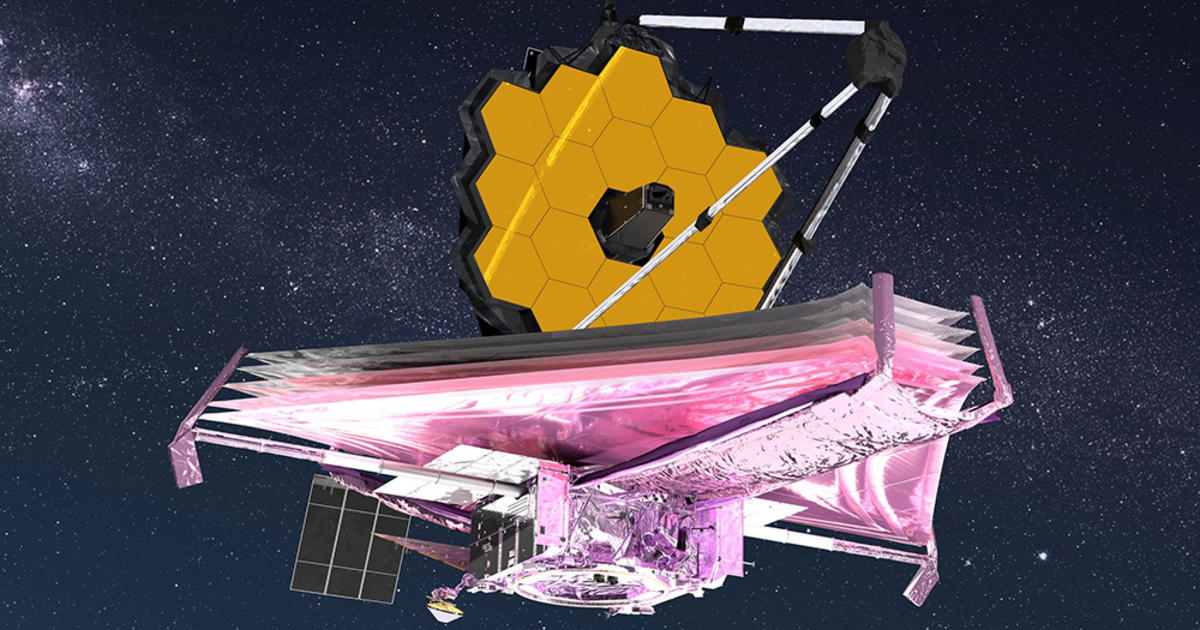

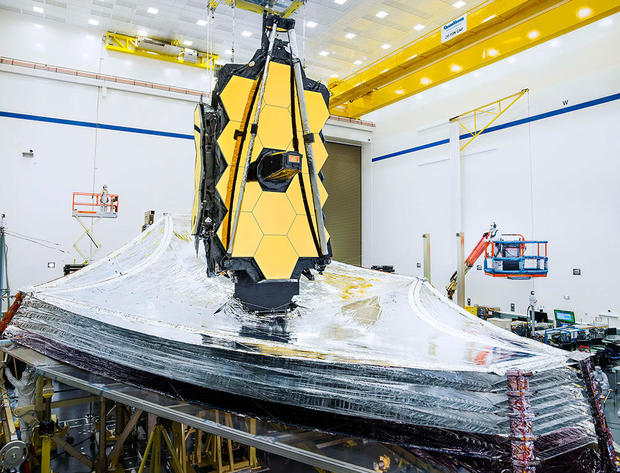

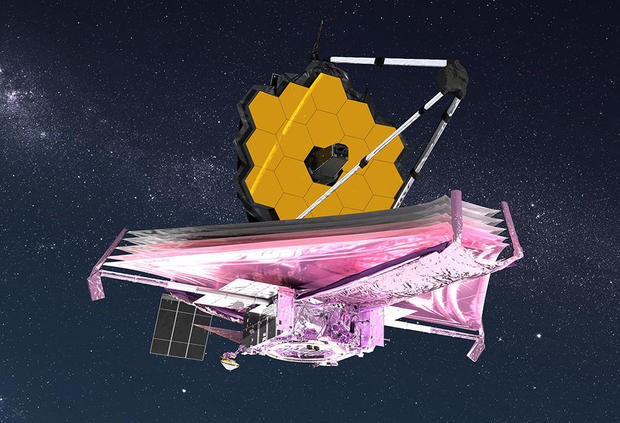

After protective covers were rolled back out of the way, two telescoping booms extended from the sunshade pallets on New Year’s Eve, pulling out the Kapton membranes into their now-iconic kite-like shape.

“The tensioning of the layers is obviously the next big step that we go through,” Ochs said. “When we complete tensioning of all five layers, we will have retired somewhere between 70 and 75 percent of those 344 single-point failures that were discussed prior to the mission.”

He was referring to the number of non-redundant devices and mechanisms required for Webb’s myriad deployments that have no backups if something goes wrong. All of them simply have to work.

NASA

The sunshade is required to block out the heat of the sun, cooling Webb’s 21.3-foot-wide primary mirror and instruments to nearly 400 degrees below zero, cold enough to register faint infrared light from the first stars and galaxies to light up after the Big Bang.

To achieve the required ultra-low temperatures, each layer must be pulled taut by motor-driven cables running through multiple pulleys, a process that also lifts and separates the membranes to allow gaps for heat to dissipate.

That final tensioning was held up over the weekend to give engineers time off after a busy first week of deployment activity and then to assess the performance of Webb’s five-panel solar array and its battery system.

As it turned out, factory presets governing the solar array’s output needed adjustment to take into account the actual temperatures Webb is experiencing in space. At the same time, the telescope was re-oriented slightly to cool six motors needed to pull the sunshade layers taut.

“Everything is hunky-dory and doing well now,” said Amy Lo, Webb systems engineer with prime contractor Northrop Grumman. “The observatory was never in danger, we were never power starved. … The rebalancing of the array gives us quite a lot of margin (for) the expected increase in power that we will be needing as we proceed on.”

As for the motors, Lo said they were never out of limits, just a bit warmer than optimum. Playing it safe, Webb was reoriented Sunday to improve cooling and “we’ve got a lot of margin now on our temperature.”

Bill Harwood has been covering the U.S. space program full-time since 1984, first as Cape Canaveral bureau chief for United Press International and now as a consultant for CBS News. He covered 129 space shuttle missions, every interplanetary flight since Voyager 2’s flyby of Neptune and scores of commercial and military launches. Based at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Harwood is a devoted amateur astronomer and co-author of “Comm Check: The Final Flight of Shuttle Columbia.”