Federal health officials are urging all vaccinated adults to get their Covid booster shot amid growing alarm over the omicron variant, a heavily mutated coronavirus strain that’s already been detected in a handful of states across the U.S. But some vaccine experts worry that numerous booster doses of existing vaccines could make future vaccines, if needed, less effective.

The variant’s mutations suggest it may be able to dodge some of the immunity provided by vaccination or natural infection. While federal health officials and drugmakers await highly anticipated lab results to see how much of a threat omicron poses to vaccines, for now, the existing boosters are the best defense against the new strain and the highly transmissible delta variant, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the White House’s chief medical adviser, epidemiologists and immunologists say.

But what is the best strategy for boosters going forward? And if boosters are needed for years to come, as Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla has suggested, will they need to be modified?

Studies show an extra dose of the current Covid vaccines “increase levels of neutralizing antibodies against all the variants,” Fauci, director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease, said Friday at the White House Covid-19 Response Team briefing. “There’s every reason to believe that if you get vaccinated and boosted that you would have at least some degree of cross-protection, very likely against severe disease, even against the omicron variant.”

This week, the health minister of Israel, which started giving out third doses of Pfizer booster shots in summer, said that a fourth booster dose might be necessary if the country’s Covid cases continued to climb.

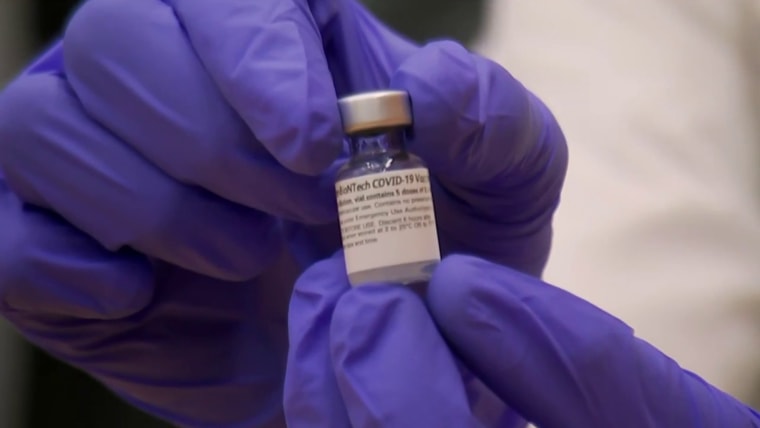

Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson are working on omicron-specific vaccines to use against the new variant if lab tests show significant declines in protection against severe disease, though it could take months before they’re ready to be distributed.

Still, there is discussion among some health experts about whether it is appropriate to use the existing vaccines as boosters against new, emerging strains, as the shots are still formulated to target the original form of the virus identified in late 2019.

“The question is, if you keep priming and boosting with a strain, which is basically to make an immune response against the ancestral strain, will that limit your ability then to make an immune response to a virus, which is very much different than the ancestral?” said Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Offit is describing a phenomenon immunologists call “original antigenic sin” in which the body’s immune system relies on the memory of its first encounter with a virus, sometimes leading to a weaker immune response when it later encounters another version of the virus.

Vaccines can activate this phenomenon, too, said Offit, also a member of the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory committee. An example is with the human papillomavirus, or HPV, following the release of an updated vaccine that targeted nine strains of the virus instead of just four in the initial shot, he said.

“If you got HPV4 and then got HPV9, knowing that the four strains in [HPV]4 were also in [HPV]9, you had a very good immune response to the four strains, but you didn’t have as good as an immune response to the other five strains,” he said.

Theoretically, it could apply to Covid, too, Offit said.

He said that some experts have argued it may be better for those not at high risk of severe disease to wait to get a booster until a variant-specific option is available.

He, along with Philip Krause and Marion Gruber, two former FDA officials, wrote an op-ed published Monday in The Washington Post that argued that booster shots should be restricted to those at high risk for severe disease, such as the elderly and those who live or work in high-risk settings, like health care workers. They said the original two doses of the mRNA vaccines are still working for most healthy adults.

Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist and former Covid adviser to President Joe Biden, countered that the third dose of mRNA or second dose of J&J should be considered part of the original vaccine’s primary series and people should get a booster as soon as eligible. A booster dose “can actually offset the immune evasion we’ve seen with this particular variant,” Osterholm told MSNBC’s Hallie Jackson on Friday.

Ali Ellebedy, an associate professor of pathology and immunology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, pointed out that for influenza as well, having too many antibodies against previous strains can interfere with vaccinations against other flu variants.

However, he said he rejects the idea that this could happen for Covid, at least right now.

The global population has not accumulated enough baseline antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 “to block any further boosting, which is the case in flu for some people,” he said. He also noted influenza vaccines are “poorly immunogenic vaccines,” nothing like the mRNA vaccines.

Ellen Foxman, an immunologist at Yale University, said even if boosting with the original vaccine did make future vaccines less effective, it is not “wise” to wait for a variant-specific shot to get a boost. The bottom line, she said, is that there’s a life-threatening virus still spreading across the country and current vaccines have been shown to protect against it.

Will the existing shot be as good as it was against the original virus? “Maybe or maybe not, but it will probably provide at least some protection against it,” she said.

Waiting for an omicron-specific booster is a very high-risk strategy.

Vaccine Researcher Dr. Peter Hotez

“If we knew that we needed an updated booster and we knew it was going to come out next week, maybe you should wait,” she said. “But the truth is, this coronavirus is going around now and it’s mostly the delta variant.”

Dr. Peter Hotez agreed, adding that the 30-to-40-fold rise in virus-related antibodies generated by the booster shots may be sufficient against the new strain.

“No matter what, you can’t wait for your booster because delta is still the dominant variant and will be so, I think, for the foreseeable future,” said Hotez, co-director of the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

He added that a variant-specific vaccine may not be needed and that there’s a chance that the omicron-specific boosters the drugmakers are developing won’t work.

“A slam dunk is not guaranteed,” Hotez said. “Waiting for an omicron-specific booster is a very high-risk strategy.”

John Moore, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the Weill Cornell Medical College, said there are still some unknowns about the uses of the vaccines, and so the “best-boosting strategy” will emerge over time.

“Everyone wants instant answers, but it matters more to get the right answers. That takes time,” he said.