Yes, some of the most apocalyptic redistricting predictions of recent years have been found wanting — many Democrats said they’d never win the House again until they got new maps after 2020; then along came Donald Trump. But the last decade of election results shows just how powerfully redistricting shapes the House of Representatives, especially when the parties control the process through their representatives in state legislatures, who can work in concert with incumbents in Washington to draw favorable maps.

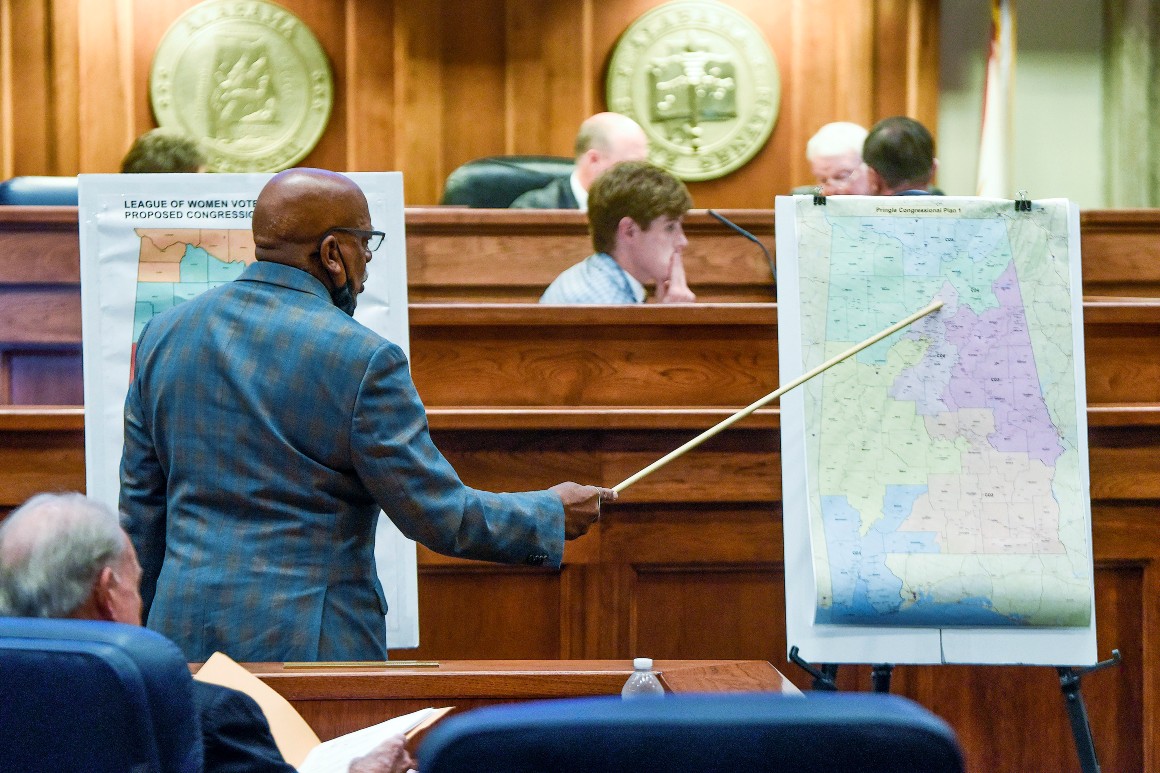

In Texas, for example, the GOP delegation presented to the state Legislature a proposal that would give Republicans at least 25 of the state’s 38 districts.

“We were able to get all the members together around a unified map and then submit it to the state Legislature,” said GOP Rep. Michael McCaul. “And they were pleased to have our input.”

That shows in the makeup of the House, as you’d expect. In each of the past three elections, most of the swing seats that changed hands between the parties came from commission- and court-drawn districts, while the congressional delegations from legislature-drawn states changed relatively little.

The most striking example is from the 2018 “blue wave,” when Democrats won control of the House. They needed to flip 23 congressional seats to flip control of the chamber. But even as the national vote swung nearly 10 points toward Democrats compared to the previous election, the party could only flip 10 seats in states where legislators drew the congressional maps. The levees built around many safe Republican seats drawn years before — even in the suburbs, amid fierce anti-Trump backlash — were higher than the crest of the wave.

That was not the case in states where commissions and courts drew the maps. Democrats netted 31 seats in those states, including longtime court-drawn battlegrounds in the Las Vegas suburbs and upstate New York, commission-made districts in California and Arizona and several seats in states, like Virginia and Pennsylvania, where courts declared old districts illegal mid-decade and replaced them with maps that included more swing seats.

What does this mean for the congressional maps of the future? The national environment, population changes and the evolution of the two party coalitions over the next decade will alter the battleground map with every election. But we can expect the bulk of swing House seats to show up in states where legislatures aren’t driving the redrawing process.

Consider Democratic-controlled Illinois and Republican-controlled Texas, for example. Majority-party legislators in both states, consulting with their congressional delegations, methodically erased as many closely divided districts as possible in their new congressional maps. In Texas, that meant axing Democratic voters out of Republican districts in the suburbs that were trending uncomfortably purple. In Illinois, that meant extending tendrils out from Chicago and linking other metro areas together to make as many strong Democratic districts as possible.

There’s much more unpredictability in the states where legislators aren’t involved. Draft maps from California’s citizen redistricting commission, for example, would cause heartburn for incumbents from both parties, though they are likely to change significantly before being adopted.

The biggest changes are likely coming in places that have changed the way they redistrict since the last decade. Michigan, for example, has a redistricting commission instead of a Legislature-led process this year. Moving in the other direction, a court drew New York’s congressional map in 2012, but Democratic state legislators appear ready to pass their own map this year (which would involve overriding the redistricting commission voters approved in 2014 to wrest the process out of their hands).

Redistricting methods won’t necessarily change in all the states where the map above shows they could. In Pennsylvania, for example, the Legislature has the power to create new maps for 2022 to replace the ones drawn in 2018 by the state Supreme Court, which threw out the old Legislature-drawn map. But the Republican state Legislature and Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf may be unlikely to reach a compromise, in which case a court could step in to draw another new map.

The state Supreme Court’s 2018 map helped usher in four new Democratic members — all women from the greater Philadelphia area. Under the old map, Republicans controlled 13 of the 18 districts for three election cycles.

“I have confidence from the last time, and a conversation with the governor, that he will veto anything that looks like a gerrymandered map or set of maps,” said Rep. Madeleine Dean (D-Pa.). “And so I hope that the [state] Supreme Court again will do what they did last time in 2018 which was — the first time in a long time — to draw fair districts at the congressional level.”

Mid-decade redistricting also caused a shake-up in North Carolina, where Republicans held at least nine of the state’s 13 seats until a court-mandated redraw gave Democrats two new pickups.

In Ohio, Republicans carved up the state so artfully that they maintained control of 12 of the 16 seats throughout the entire last decade. GOP Rep. Steve Chabot’s district slices up Cincinnati’s Hamilton County so well that it didn’t even flip in 2018, when a blue wave overwhelmed dozens of suburban Republican districts in other states.

Republicans still have total control over the redistricting process in Ohio, but other Midwestern states might prove more fruitful for Democrats. States where one party controls one or both houses of the legislature and the other controls the governorship, like Wisconsin and Minnesota, could easily end up getting court-drawn maps as well.

States like those could be the sites of future battles for control of the House over the next decade. In many of the others, redistricting will ensure that little changes from election to election.