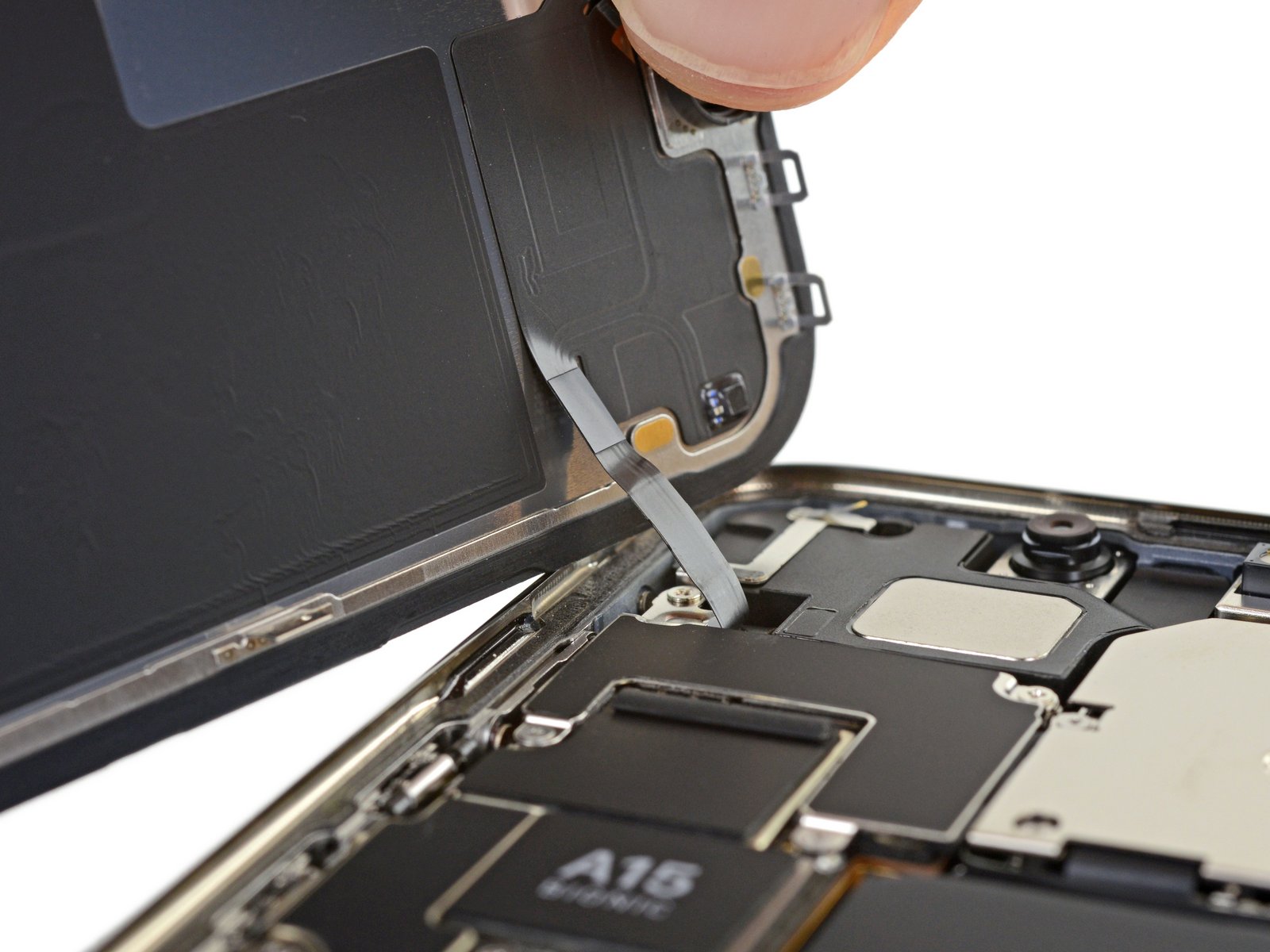

Apple does not have a good track record in terms of letting customers repair their hardware. The last decade-plus has seen Apple’s computers become essentially impossible for users to service or upgrade, and the iPhone has always been a locked box. Adventurous owners might follow guides from iFixit to try and do repairs themselves, but it’s a dangerous proposition. Remember, it was just earlier this year, when we discovered that replacing the display on an iPhone 13 would disable Face ID (something Apple eventually made an about face on).

So Apple’s announcement earlier this week that it would start selling parts and tools directly to consumers and offer repair guides was a huge surprise, and a move immediately hailed as a victory for right-to-repair activists. “One of the most visible opponents to repair access is reversing course,” said Nathan Proctor, a senior Right to Repair campaign director at Public Interest Research Groups (PIRG). “Apple’s move shows that what repair advocates have been asking for was always possible.” iFixit was similarly pleased, saying that the move is “exactly the right thing for Apple to be doing.”

Both groups caveated their statements by noting a few catches; PIRG says that Apple’s plans weren’t as comprehensive as the right-to-repair legislation being discussed in more than two dozen states, while iFixit wants to “analyze the legal terms and test the program” before it can say just how much credit Apple deserves. But regardless, it’s still a major about-face. So what led Apple to this move?

Proctor told Engadget in an email exchange that he thinks “combined pressure from consumers, regulators and shareholders has shifted Apple’s thinking.” But he was also quick to point out that there was pressure coming from inside Apple itself. “We saw from some leaked emails from 2019 that many inside Apple never wanted to be hostile to repair in the ways that Apple has been at times,” he said. You probably saw that [Apple co-founder Steve] Wozniak called [out] the practices, but leaked emails show internal concern they were doing the wrong thing.”

Apple has made some other movies recently that show that potential government scrutiny and oversight could be driving change at the company. In 2020, Apple finally let users set different browser and email apps as default on the iPhone and iPad, and Siri has gotten smarter about learning your preferences for different music apps when you ask it to play tunes.

While it’s likely that Apple is thinking about government pressure, this change might also simply be part of the company listening to its users and correcting some mistakes it made over the last five years or so. Take the new MacBook Pro, perhaps the biggest “mea culpa” Apple has ever offered; the company reversed its trend of pursuing thin and light design at all costs and instead actually made the both the 14- and 16-inch MacBook Pros thicker and heavier than their predecessors. The company also added back ports it had previously removed, killed the unpopular Touch Bar, and generally made a laptop that made it seem like they were listening to consumer feedback. The same could be said for its new home repair program.

Regis Duvignau / Reuters

Apple’s move this week can also be seen as an extension of a program the company launched last year, when it started providing parts and training to third-party repair shops that met Apple’s qualifications. Obviously, this isn’t the same as making it easy for anyone to do repairs, but opening up access means the repair landscape for Apple products has changed significantly in the last few years.

However big of a change this new plan is, though, Proctor and PIRG see this as a first step, something Apple will need to keep up and expand to really meet what right-to-repair activists think consumers deserve. “I think Right to Repair knows what it wants, and it will be really hard to convince us to settle for anything less than an open market for repair,” Proctor said. “If they had done this step years ago, maybe we would have to settle, but we have the momentum, and we are going to empower repair as much as we can. I think most legislators agree: this is just one company and a limited program. The floor got raised, but we aren’t near the ceiling yet.”

iFixit has a similar view on the situation. “[Apple] pioneered glued-in batteries and proprietary screws, and now they are taking the first steps on a path back to long-lasting, repairable products. iFixit believes that a sustainable, repairable world of technology is possible, and hope that Apple follows up on this commitment to improve their repairability.”

As for what’s to come, it sounds like Apple is committed to making this just a first step. The company said that repair options would initially focus on commonly-repaired modules in the iPhone 12 and 13, like the screen, battery and cameras, but it says that more options will come in the following year. We don’t know if Apple will ever give right-to-repair activists everything they want. It seems unlikely that Apple will make an iPhone where you can just pop it open and drop a new battery in, like the phones of old.

Apple can often be a bellwether for the rest of the industry — just look how quickly other phone-makers dropped their headphone jacks. So, it’s possible we’ll see some other big consumer electronics companies make similar moves. “I think other companies will follow,” Proctor said. He also noted that Google had just released software that lets a replacement display on the Pixel 6 be properly calibrated to work with the in-screen fingerprint sensor.” We see a lot of changes in the works, and we are hopeful we can set a new baseline [for] access to repair.” If that happens, we’ll likely remember Apple’s about-face as a major catalyst for these changes — assuming the company follows through with its new stance and makes it easier for owners to repair a wider variety of its products.

All products recommended by Engadget are selected by our editorial team, independent of our parent company. Some of our stories include affiliate links. If you buy something through one of these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.