Strategic Resource Group managing director Burt Flickinger argues Americans are experiencing ‘one of the worst crises in modern retail history that we’ve seen and it has all evolved in less than a year.’

American consumers are coping with the hottest inflation in more than three decades, with the cost of everyday necessities like food, rent and heating oil surging in recent months.

And there’s no evidence the monthslong inflation spike is slowing down: On Wednesday morning, the government reported that prices for U.S. consumers surged 6.2% in October compared with a year earlier. So-called core prices, which exclude the more volatile measurements of energy and food, rose 4.6% over the past year. Both are the largest increases since 1990. From September to October, prices jumped 0.9%.

“I expect lots of eyeballs were bulging out of their sockets when they saw the number come in,” said Seema Shah, chief strategist at Principal Global Investors. “Inflation is clearly getting worse before it gets better.”

Rising inflation is eating away at strong gains and wages and salaries that American workers have seen in recent months (average hourly wages in the U.S. actually fell 1.2% last month compared with October 2020 when accounting for inflation).

The price squeeze has been bad news for both Biden administration officials as well as Federal Reserve policymakers, many of whom have been downplaying the recent spike in consumer prices as “transitory” and likely to abate as pandemic-induced disruptions in the supply chain faded.

That sanguine viewpoint was challenged once again this week by a significant jump in the price for a wide range of items: Gasoline skyrocketed by nearly 50% in the year to October, meat was up 14.5% and rent increased by 3.5%.

Fueling the price spikes are several issues related to the pandemic and the rousing economic rebound from the worst downturn in nearly a century. In the wake of lockdown orders that saw a broad swath of the country shut down, the economy staged a stunning comeback, powered by unprecedented levels of government spending, emergency steps by the Fed and the widespread distribution of vaccines.

As Americans – flush with stimulus cash – ventured out to shop, eat and travel, businesses struggled to meet the demand, reporting difficulties in onboarding new employees and buying enough supplies to satisfy the need. Many businesses, in order to attract new talent, hiked wages – but to offset those increases, employers have reported raising the prices of their products.

The matter was further complicated by bottlenecks at ports and freight yards, along with a lack of shipping containers, snarling the global supply chain.

“A perfect storm of supply chain disruptions, labor market shortages and higher energy prices have combined to bring annual inflation back to levels last seen in the very early 1990s,” said Matthew Sherwood, a global economist at the Economist Intelligence Unit. “That is unlikely to change anytime soon.” Sherwood predicted that inflation on a year-over-year basis could remain above 6% until “at least the spring.”

But the massive levels of government spending that Congress threw at the pandemic – including a $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package that President Biden signed into law earlier this year – is likely stoking hotter inflation, according to research published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco last month.

WHERE IS SURGING INFLATION HITTING AMERICANS THE HARDEST?

The San Francisco Fed paper found that the American Rescue Plan played a role in contributing to the inflation spike, but concluded the nearly $2 trillion plan will ultimately have a modest long-term effect on it. The economists estimated the plan would add 0.3 percentage points to the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge (known as the Personal Consumption Expenditures inflation index) in 2021 and “a bit more than” 0.2 percentage points in 2022.

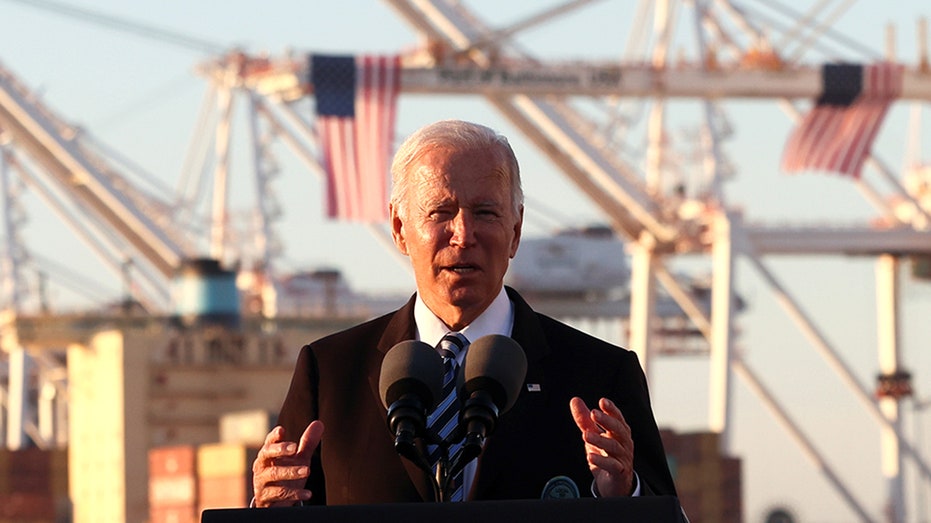

In a statement Wednesday, Biden acknowledged that “inflation hurts Americans’ pocketbooks, and reversing this trend is a top priority for me.” But he repeated previous claims that a bipartisan $1 trillion infrastructure package, which allocates billions to “core” projects on roads, bridges and transit, would help ease supply disruptions.

It’s unclear when consumers can expect to see inflation begin to slow.

Chairman Jerome Powell has repeatedly maintained that inflation is “transitory” and blamed disrupted supply chains, pent-up consumer demand and stimulus cash for the run of higher prices. But he’s modified his tone in recent weeks, acknowledging that surging inflation may not fade until the second or third quarter of 2022.

“Our baseline expectation is that supply bottlenecks and shortages will persist well into next year and elevated inflation as well,” Powell told reporters. “And that, as the pandemic subsides, supply chain bottlenecks will abate and job growth will move back up. And as that happens, inflation will decline from today’s elevated levels.”

In an analyst note to clients on Sunday, Goldman Sachs economists warned that pandemic-induced disruptions in the global supply chain could last longer than expected as surging demand struggles to keep up, meaning that inflation metrics will remain “quite high for much of next year.”

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

The Goldman Sachs economists projected that core PCE inflation, the Federal Reserve’s preferred gauge, will rise from 3.6% to 4.4% by the end of 2021. They have forecast that inflation will cool slightly to 2.3% at the end of 2022 and fall to 2.1% by the end of 2023.

“It is now clear that this process will take longer than initially expected, and the inflation overshoot will likely get worse before it gets better,” they wrote.